October 16, 2015

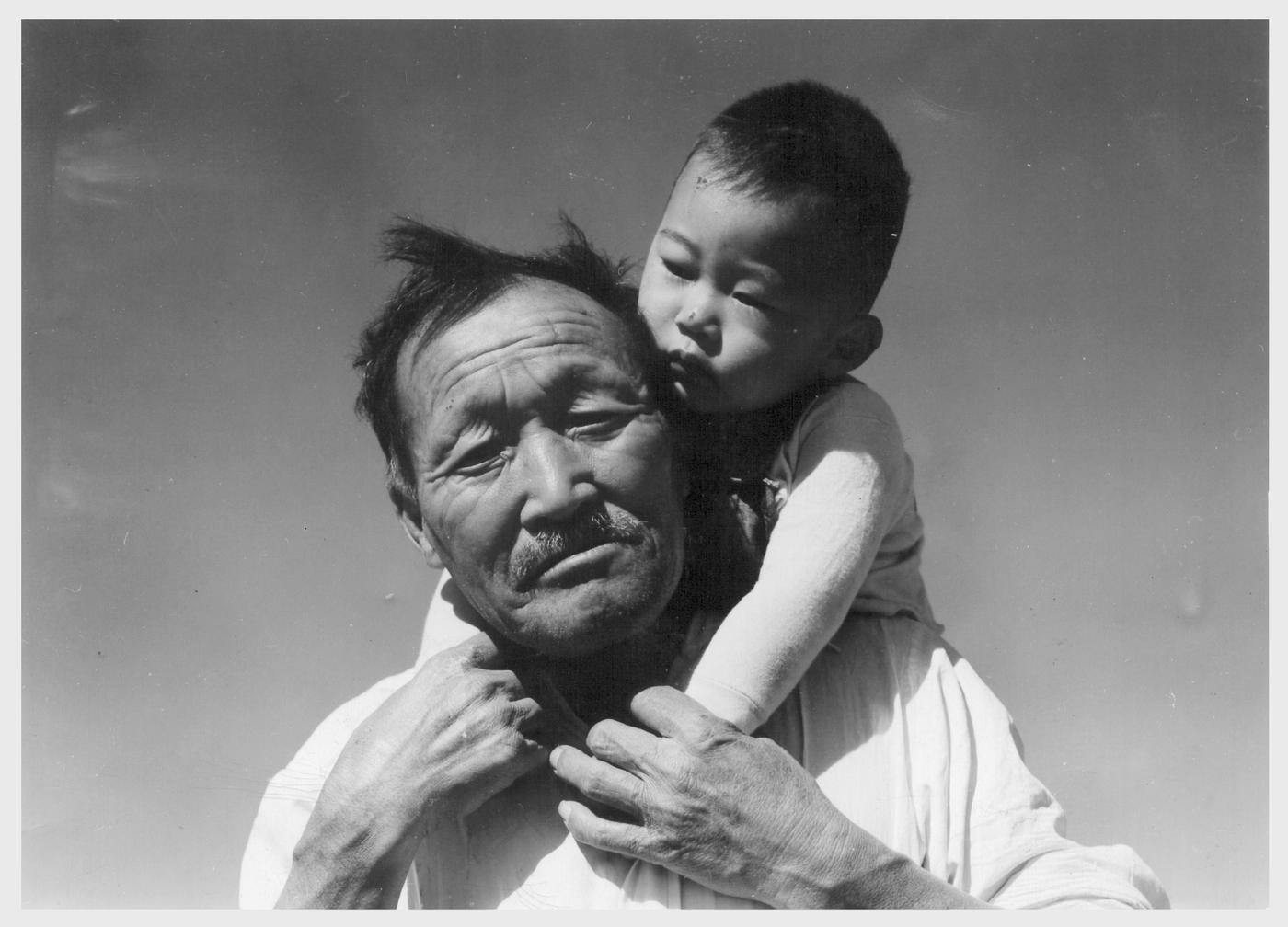

Since then, he has been inspired by the strength and spirit of his parents’ and grandparents’ generations. Committed to preserving the stories of this generation, he conceived of a photography project that would capture their resilience and ability to triumph over adversity. That project will make its Pacific Northwest debut in a new traveling exhibit, Gambatte! Legacy of an Enduring Spirit, which opens Saturday, October 17 at the Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center.

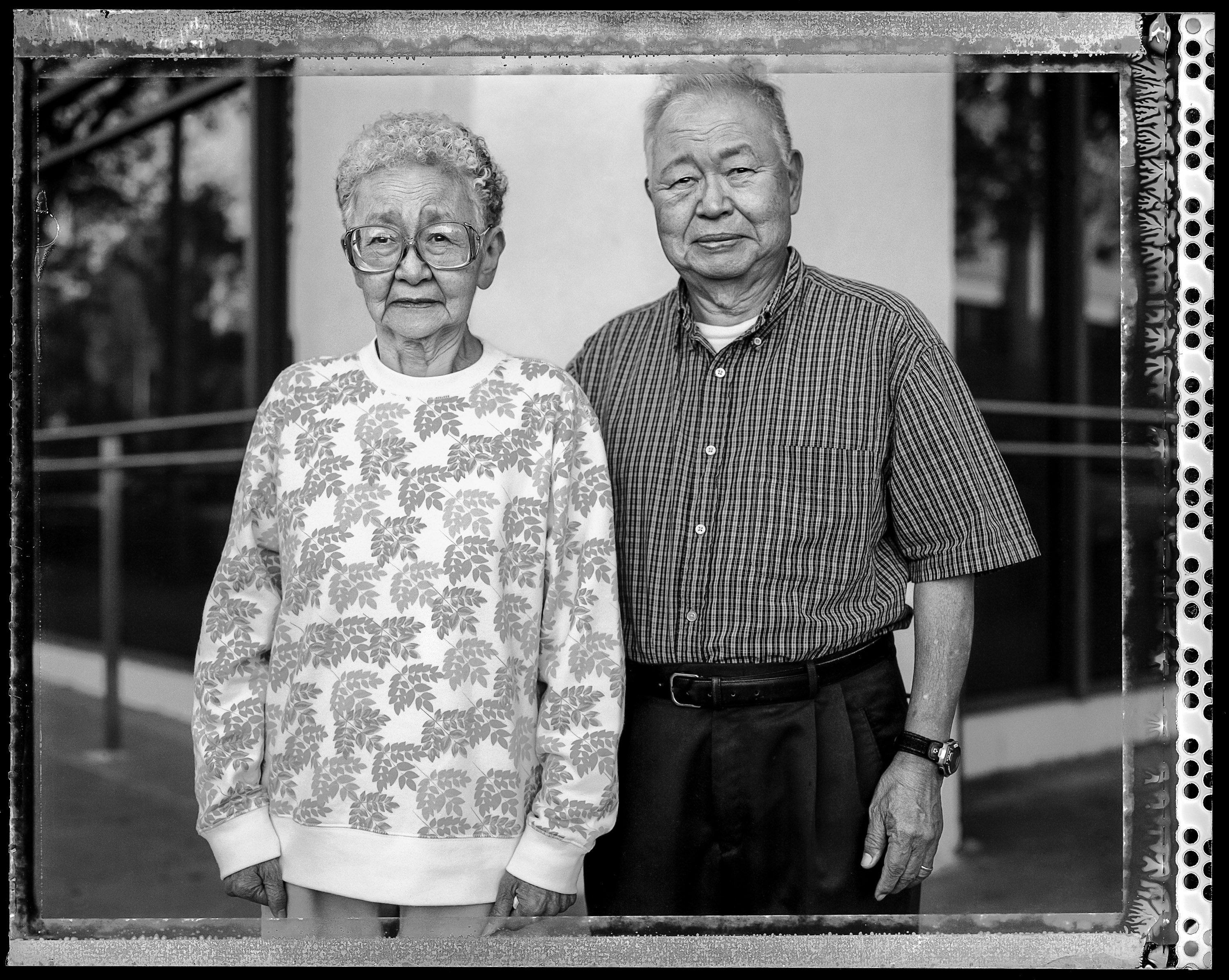

The show features side-by-side contemporary and historic portraits of individuals and families photographed by War Relocation Authority staff photographers, including Dorothea Lange, during WWII incarceration and decades later, photographed in some of the same locations by Kitagaki.

Here, Kitagaki responds to questions Densho staff posed to him and shares family portraits taken by Dorothea Lange and himself.

[Header photo caption: A selection of portraits in Kitagaki’s “Help Find Missing Internees” photo gallery.]

Densho: At the core of your project is an effort to preserve and share stories about Japanese American WWII incarceration. What made you decide this was an important thing to do?

Paul Kitagaki, Jr.: In conversations with a wide range of people from regions across the United States, many do not remember learning about the incarceration during WWII. In many public and private schools across the nation, this chapter of American history is rarely being taught. This exhibit offers a visual opportunity to learn about this time in history and to educate a new generation of gatekeepers, as well as the older generations, about the tragedy of war and the importance of standing up for the Constitutional rights of all people. Although the Japanese American incarceration occurred 70 years ago, current events such as the crisis in the Middle East and the racial turmoil in the U.S. reveal that the message of this exhibit is more relevant than ever.

I hope that future generations will be inspired by these stories and images. Their perseverance in overcoming the many hardships in their lives has produced the opportunities enjoyed by my Sansei generation and the generations of my children and their children.

You must share so many poignant moments in bringing people back to the sites where WRA staffers originally photographed them. Is there one experience that really stands out to you that you could share with us here?

PK: I had some people well up with tears and emotion during the interview. This was the first time for some of them to speak publicly about their experience. You have to remember that many Sansei, third generation Japanese-Americans, never heard the stories of the incarceration and the emotional and financial toll it took on their parents and grandparents. Many of the Issei and Nisei generations didn’t share their stories with their own families. I learned of my family’s incarceration during a high school history class in 1970, since growing up my parents hadn’t spoken of it.

I imagine that identifying individuals and then tracking them down was a major challenge. How did you go about doing that? Are there people you’re still looking for?

PK: It has been a tremendous challenge to identify people in a photograph taken over 70 years ago with very little information or names about the people in the photographs. I have been searching for over ten years for the identity of many of my subjects. Once a name was connected with an image I had to persuade the participant to talk about their experience. Many of the survivors still found it very difficult to talk about that time in their lives. They wanted to move on and not burden their children with the shame they endured so many years ago.

I started by taking the photographs to churches in Sacramento and was able to identify some of the people in the photographs. Some of my leads came from people who knew I was looking for subjects and they were able to help me connect with them. Once I had been given a name, I had to figure out where this person might be living and if they were still alive. I was extremely lucky when somebody knew the identity of the people in the photograph from the 1940’s and contacted me. With the generosity of many people I have been able to find over 40 people.

I am still looking for more subjects from the War Relocation Authority photographs and other photographs taken during the incarceration experience. That could be before the evacuation, during camp and resettlement after the end of the war. Time is of the essence as many of the subjects who were children during the incarceration are now in their eighties and nineties and many have already passed away with their stories lost forever. I am still able to tell the story of some using their descendants to tell their family’s story. There are over 9,000 images in the JARDA Japanese American Relocation Digital Archives at the UC Berkeley Bancroft Library.

As an artist, how do you think your work speaks to broader conversations about the lasting legacy of WWII incarceration or the resilience of the Japanese American community?

PK: I am photojournalist who is also an artist. I think my exhibition presented in a documentary style gives the subjects a platform for their voices and stories—silent for many years—of a shared experience living in the United States. I strive to create contemporary images that complement and mirror the original photographs of Lange and her counterparts and reveal the strength and perseverance of my subjects. Most importantly, I wanted to know how Executive Order 9066 forever changed the lives of these internees who unjustly lost their homes, businesses and, sometimes, their families. How did this one tragic event in history change these peoples’ lives forever.

You mentioned that you found Lange’s photographs of your own family while conducting research in the National Archives. How did you make this discovery and what was it like to encounter images of your family?

PK: When I was starting out as a photographer in 1978 my uncle, Nobuo Kitagaki, an artist in San Francisco told me that Dorothea Lange had taken photographs of my grandparents Suyematsu, 65, and Juki, 53, dad Kiyoshi, 14, and aunt Kimiko Kitagaki, 12.

In 1984, I was in the National Archives in Washington, DC and looked through over 900 4×5 images in archival boxes and discovered my family. I was astonished and couldn’t believe it. My family was recorded during a major historical event by one of my hero photographers, Dorothea Lange. As I examined Lange’s work, I realized that every photograph represented an untold story that was quietly buried in the past. I had many questions and few answers.

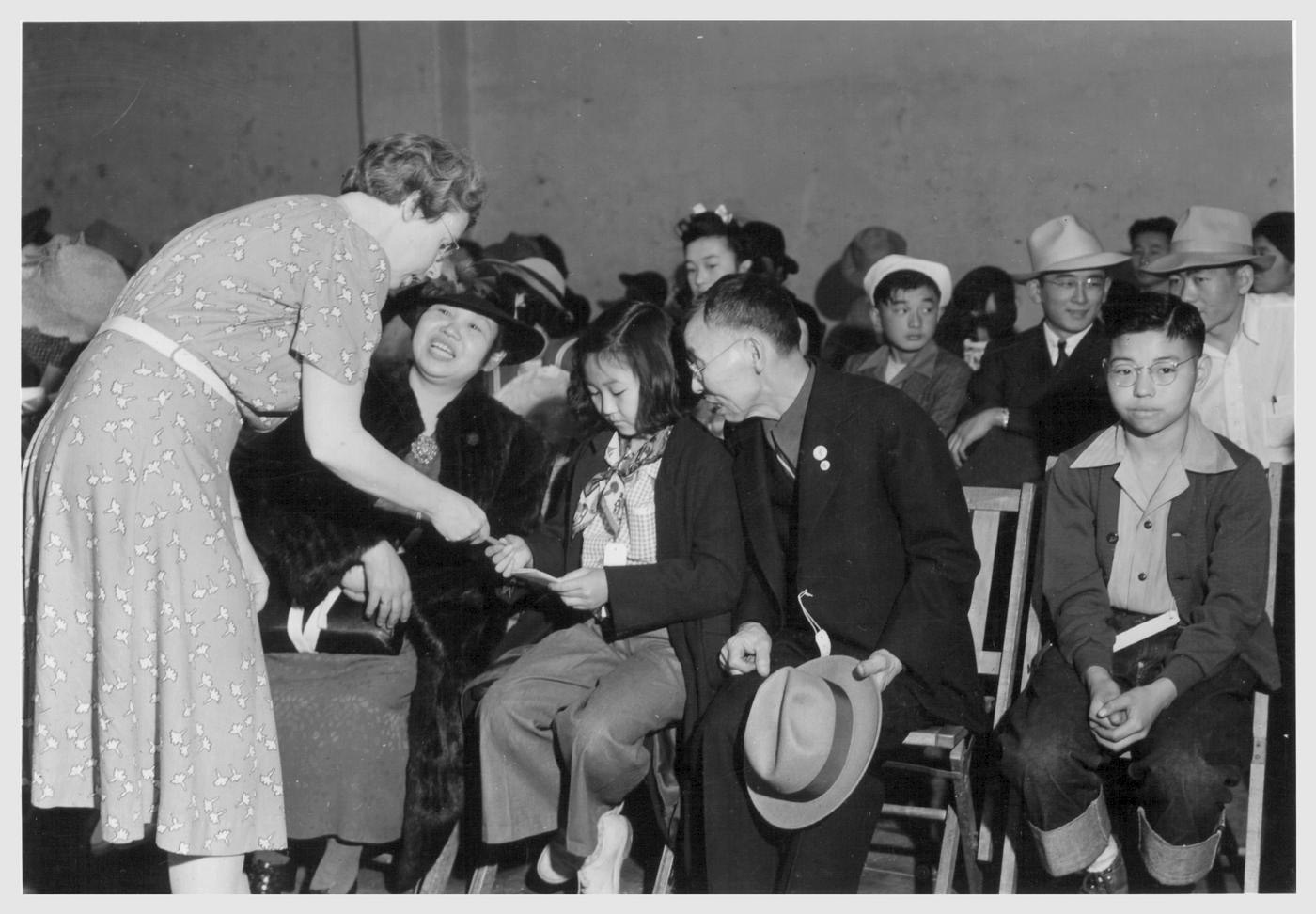

It was shocking to find them there. My grandparents are on the left smiling and talking to a Caucasian woman. And there was my father on the right looking at the camera. Dad—dazed, sad, shocked, looking like he is wondering what is coming next. I later found out that my grandparents knew the woman who they were talking to really well, which explains why they are so happy to see her.

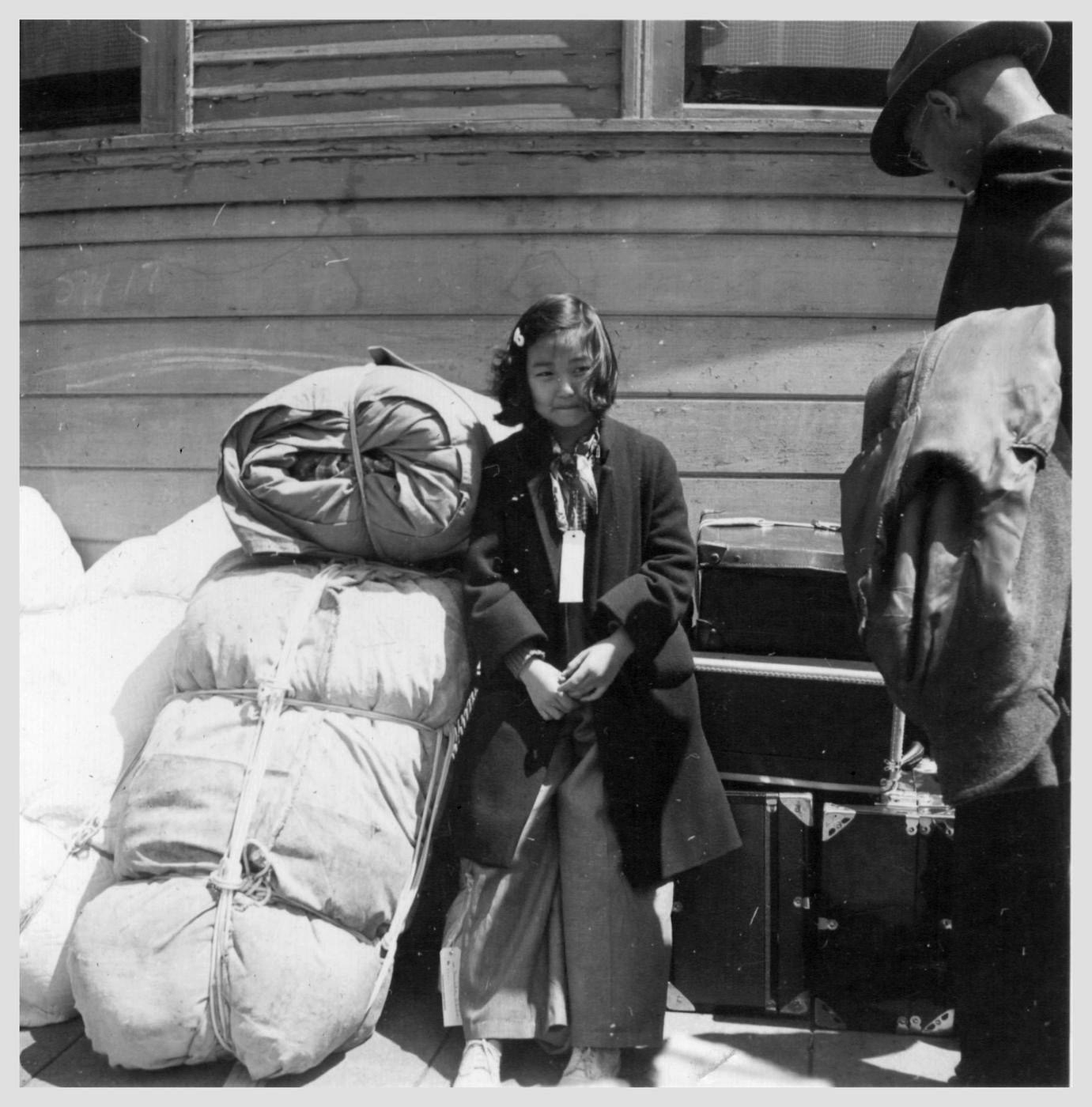

There are two more images of my aunt Kimiko standing with luggage, which was also feature during the Smithsonian exhibition A More Perfect Union about the Japanese Americans and the U.S. Constitution. As I flipped thought the boxes of images I realized the boxes held many untold stories of the incarceration, stories that needed to be told before they were gone.