July 28, 2016

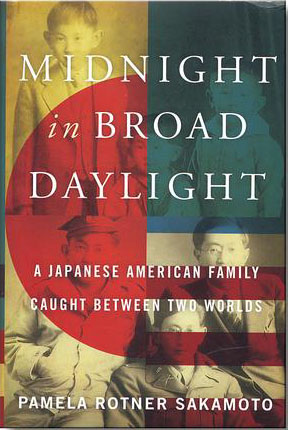

A new book, Midnight in Broad Daylight: A Japanese American Family Caught Between Two Worlds by Pamela Rotner Sakamoto, follows the relatively prosperous Fukuhara family of Washington state as their fortunes are dramatically changed by the untimely death of the Issei patriarch in 1933.

A new book, Midnight in Broad Daylight: A Japanese American Family Caught Between Two Worlds by Pamela Rotner Sakamoto, follows the relatively prosperous Fukuhara family of Washington state as their fortunes are dramatically changed by the untimely death of the Issei patriarch in 1933.

The Issei mother subsequently moves with her children to Japan, and the adult Nisei children end up on opposite sides of the war a decade later. Three brothers are conscripted into the Japanese army while two siblings are in the U.S. One of the latter, Harry Fukuhara, leaves Gila River to volunteer for the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) and ends up in the South Pacific, where the prospect of encountering his brothers on the battlefield becomes very real.

Other than to say that the book is both meticulously researched utilizing both English and Japanese language sources and beautifully written by a professional historian of modern Japan, I’m not going to review the book since, in one of the odd coincidences that have marked the twenty years I’ve lived in Honolulu, the author turned out to be my daughter’s high school history teacher!*

One thing the book does not have, though, is a bibliographic essay on the largely neglected topic of Nisei in Japan before, during, and after the war. Though we have seen more on this topic in the last decade or so, it remains effectively the missing chapter in the Japanese American World War II story, especially given the enormous amount of literature on the forced removal and incarceration and on Nisei in the U.S. armed forces.

It is not hard to imagine why this would be. The grand narrative of Japanese American history promulgated since the end of the war has been one of universal “loyalty,” Nisei men volunteering for military service out of concentration camps, and discrimination falling by the wayside after the war, allowing Japanese Americans to become a “model minority.” The story of the “strandees”—the period term for Nisei trapped in Japan when passage back to the U.S. was effectively cut off from late 1941 until a year two after the war ended—doesn’t easily fall into this narrative. Among the 10,000 or so such Nisei, a good number lost their U.S. citizenship due to voting in Japanese elections or serving in the Japanese armed forces. In the immediate postwar period—and possibly even today—the two most famous strandees were Nisei convicted of treason, Iva Toguri d’Aquino and Tomoya Kawakita. I think the JA community made a concerted effort to keep quiet about such stories, particularly as the redress movement began in the early 1970s.

Nikkei Life in Japan

Among the works on the strandees, Eiichiro Azuma’s Between Two Empires: Race History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America (Oxford University Press, 2005) and John Stephan’s Hawaii under the Rising Sun: Japan’s Plans for Conquest after Pearl Harbor (University of Hawaii Press, 1984) discusses the experiences of Nisei in Japan prior to the war, including special schools that were set up for their benefit. Yuji Ichioka edited an issue of Amerasia Journal (Vol 23, No. 3, 1997) focusing on the story of Nisei in Japan during the war years that includes interviews with four such Nisei, along with his own article on Buddy Uno, a Nisei journalist who lived and worked in Japan through the war years. Uno, the older brother of postwar activists Edison and Amy Uno Ishii, had a brother, Howard, in the MIS who encountered Buddy as a POW in the Pacific War. This episode is also recounted in Brian Masaru Hayashi’s ‘For the Sake of Our Japanese Brethren’: Assimilation, Nationalism, and Protestantism among the Japanese of Los Angeles, 1895-1942 (Stanford University Press, 1995). Mary Tomita’s Dear Miye: Letters Home from Japan, 1939-1946 (Stanford University Press, 1995) is a collection of letters home from a Nisei strandee.

Serving in the Japanese Army

There are several accounts of Nisei conscripted into the Japanese army. Jim Yoshida, a Seattle Nisei football star before the war who ended up a strandee, wrote a memoir (with Bill Hosokawa), The Two Worlds of Jim Yoshida (Morrow, 1972), centering on his forced service in the Japanese army. As one would expect given the participation of JACL stalwart Hosokawa, the tale improbably becomes one that supports the Nisei-as-superpatriot narrative as Yoshida’s Japanese coercive military service is “redeemed” by his determination to serve in the Korean War on the American side. A novel with a somewhat similar (though less theatrical) plot line about another Seattle Nisei who ends up in the Japanese army, George Nakagawa’s Seki-nin (Duty Bound) (California State University, Fullerton, Oral History Program, 1989) appeared shortly after the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. Tomi Knaefler’s Our House Divided: Seven Japanese American Families in World War II (University of Hawaii Press, 1991) looks at several families from Hawaii who were split up during the war, a number of which include Nisei involuntarily conscripted into the Japanese army. (One of them is my mom’s family; my uncle was one of the Nisei who ended up in the Japanese army.) Iwao Peter Sano’s 1,000 Days in Siberia: The Odyssey of a Japanese American POW (University of Nebraska Press, 1997) is about a Nisei strandee in the Japanese army who ends up captured by the Russians. Floyd C. Watkins’ “Even His Name Will Die: The Last Days of Paul Nobuo Tatsuguchi” (Journal of Ethnic Studies 3.4 (Winter 1976): 37-48) is about the death of a Nisei soldier in the Japanese army.

Another novel, John Hamamura’s Color of the Sea (Thomas Dunne Books, 2006) features a Kibei protagonist who teaches at the Military Intelligence Service Langauge School, then ends up in Japan at the end of the war and another Nisei character who goes to Japan with her family just prior to the war and ends up a strandee, with much description of her life as a Nisei in wartime Japan. The Kibei protagonist of Naomi Hirahara’s popular series of mystery novels, Mas Arai, also spends the war years in Japan and survives the atomic bomb; the first novel in the series, Summer of the Big Bachi (Bantam/Dell, 2004), has a plot that revolves around the contemporary implications of events that took place right after the bombing. Finally, there is a 2011 documentary film by Mary McDonald and Thomas McDonald Mazawa titled Nisei Stories of Wartime Japan, which features interviews with ten strandees, among them, the authors Tomita and Sano mentioned above.

A Precursor to Midnight in Broad Daylight

But the clearest precursor to Sakamoto’s book is Toyoko Yamasaki’s Futatsu no Sokoku/Two Homelands. Published in 1983 in Japan, the sprawling novel was a best seller in Japan and inspired the 1984 television series, Sanga Moyu, which aired over the course of the full year in 51 weekly episodes. It was only recently published in English translation by V. Dixon Morris by the University of Hawai’I Press in 2008. The central character of the book is Kenji Amo, a Kibei who returns to the U.S. at about age 20 who becomes a journalist and community leader before the war, goes to Manzanar, volunteers to be an MIS instructor, goes into combat in the Pacific, and becomes one of lead translation monitors at the Tokyo War Crimes trials before committing suicide shortly after. Though it sounds incredible, Kenji was actually based on a real person, David Akira Itami, about whom all of the above is also true. In the book, Kenji has a younger brother who volunteers for the 442nd out of Manzanar and is killed in Europe and another brother who is a strandee and conscripted into the Japanese army; since this is a novel, Kenji of course meets his brother in battle in the Philippines. Though Itami did not have brothers, Yamasaki reportedly based this part of the story on Harry Fukuhara—the main protagonist of Sakamoto’s book—whom she interviewed for her book. (Though Kenji—like his real life model Itami—are from Kagoshima, his girlfriend in the book is a Nisei from Hiroshima who returns against her will with parents who answered “no-no” and repatriated; all are killed in the atomic bombing.) A recent Ph.D dissertation—Michael Jin’s “Beyond Two Homelands: Migration and Transnationalism of Japanese Americans in the Pacific, 1930–1955” (Ph.D. dissertation, UC Santa Cruz, 2013)—is perhaps the best work ever on the Kibei and includes much on the novel and on Itami.

Coming as it did in the midst of the redress movement, the book/TV show was very controversial among JAs, with Clifford Uyeda in particular leading a campaign against it and leading the JACL to successfully prevent the TV series from being shown in the continental US. (It did get shown in Hawai’i.) As historian Yuji Ichioka wrote in Japanese American vernacular newspapers of the time, “[w]hat Yamasaki has done is to manipulate Japanese-American history, cynically and callously. She has used the Japanese American experience with white racism to stir up anti-Americanism in order to goad her contemporaries to reevaluate their received notions of about Japanese militarism. The cumulative effect of the novel is to arouse self-righteous indignation which can be rationalized to absolve Japan of any responsibility for the Pacific War.”**

The d’Aquino and Kawakita stories have come to dramatically different ends. The former was clearly a scapegoat and victim of the times and a successful effort by the JA community in the mid-1970s to secure a presidential pardon for her became an important precursor to the redress movement. There is a small cottage industry of books about her case, the most recent being Yasuhide Kawashima’s The Tokyo Rose Case: Treason on Trial (University of Kansas Press, 2013). Kawakita’s case on the other hand has largely been forgotten, with the only English language academic treatment appearing as a chapter in Naoko Shibusawa’s America’s Geisha Ally: Reimagining the Japanese Enemy (Harvard University Press, 2006).

Sakamoto’s portrayal of Nisei life in Japan before, during, and after the war are a valuable addition to this limited literature. But we have much more to learn about the group of Japanese Americans who may have faced the most difficult set of circumstances of any of their peers.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

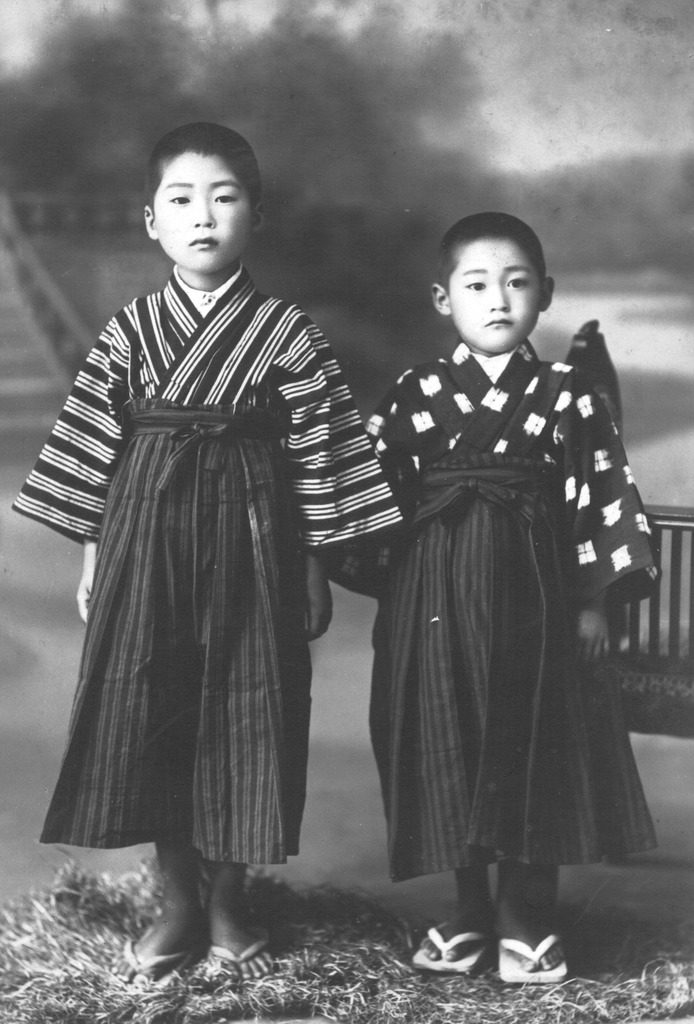

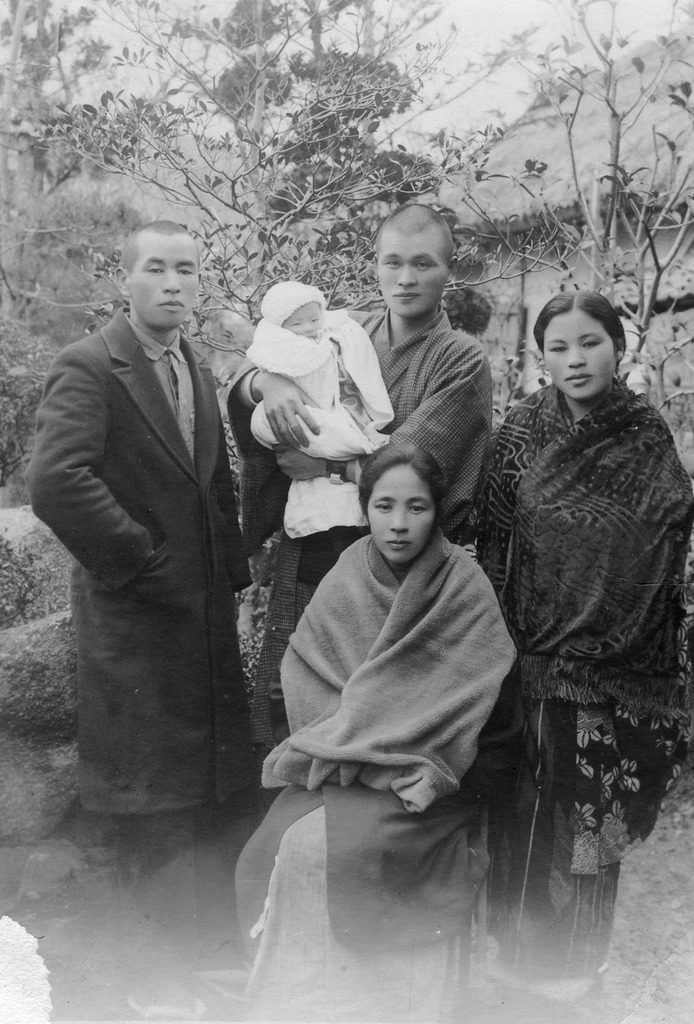

[Header image: Roy Matsumoto’s siblings were born in the United States, but went to live in Japan. Left to right: (in chronological order) Takeshi, Tsutomu, Noboru, Harue, Isao, and Shizue. Hiroshima, 1936. Courtesy of the Matsumoto Family Collection.]

* There have been so many such coincidences, that I think it may be wrong to even call them “coincidences”; such connections may just be the inevitable result of living in a small and highly interconnected society where one has many family members.

** And yet, reading the book in translation thirty-something years later and outside of the context of the redress movement, I found it quite compelling. The Issei and Kibei characters are generally well-drawn, the portrayal of the incarceration convincing, and the mixture of fictional characters with real historical figures (and characters clearly based on real people) is entertaining. At the same time, the portrayals of non-Kibei Nisei are laughable (as Ichioka puts it, they are ” monstrous mutations… who have lost their Japaneseness and claim to membership in the Japanese race”) and the last third of the book in particular does double down in portraying Japan as a victim of the war.