November 24, 2015

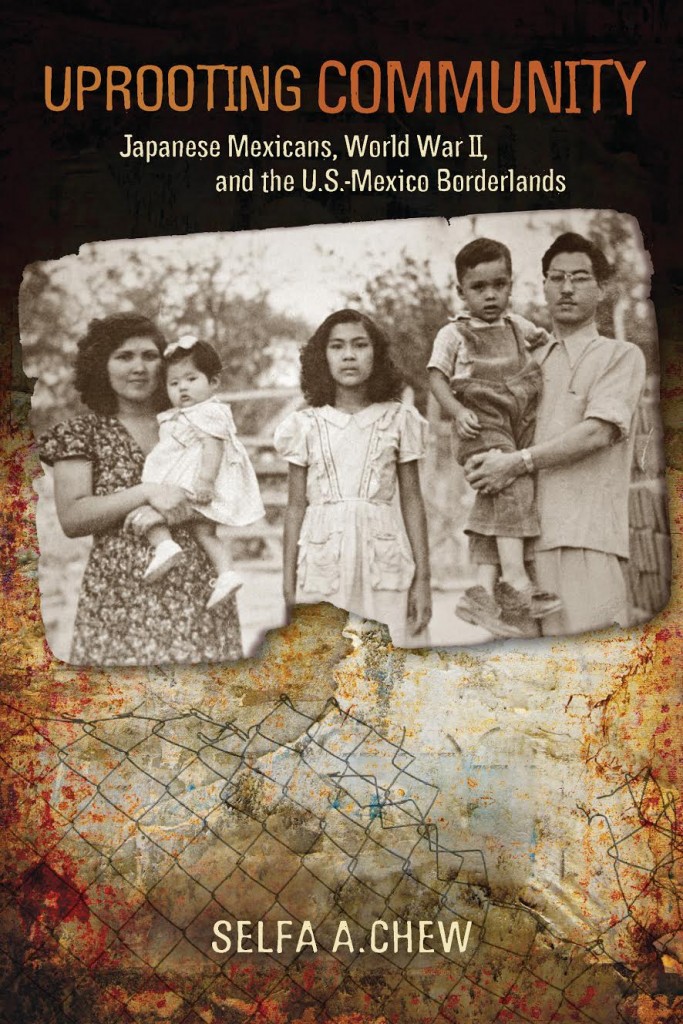

These narratives challenge the notion that Japanese Mexicans enjoyed the protection of the Mexican government during the war and refute the mistaken idea that Japanese immigrants and their descendants were not subjected to internment in Mexico during this period. Through her research, Chew provides evidence that, despite the principles of racial democracy espoused by the Mexican elite, Japanese Mexicans were in fact victims of racial prejudice bolstered by the political alliances between the United States and Mexico. Here, we feature a series of short excerpts from the book, courtesy of the University of Arizona Press.

Indicating the urgency of addressing the status of Japanese Mexicans, President Avila Camacho reported to the nation his government’s actions against “the enemy” in his presidential address of 1942. In Avila Camacho’s words, Mexico was spun as a heroic people facing open war against Italy, Germany, and Japan “because the entire nation has demonstrated with its attitude that, when the time arrives, each Mexican knows how to be a soldier determined to defend the motherland, by taking the arms or at their place of work; through productivity or through sacrifice (Applause).” The “defense of the motherland” consisted of the expulsion of Japanese Mexicans and their descendants from the borderlands and the coastal zones. [Excerpted from pp.63-64]

Indicating the urgency of addressing the status of Japanese Mexicans, President Avila Camacho reported to the nation his government’s actions against “the enemy” in his presidential address of 1942. In Avila Camacho’s words, Mexico was spun as a heroic people facing open war against Italy, Germany, and Japan “because the entire nation has demonstrated with its attitude that, when the time arrives, each Mexican knows how to be a soldier determined to defend the motherland, by taking the arms or at their place of work; through productivity or through sacrifice (Applause).” The “defense of the motherland” consisted of the expulsion of Japanese Mexicans and their descendants from the borderlands and the coastal zones. [Excerpted from pp.63-64]

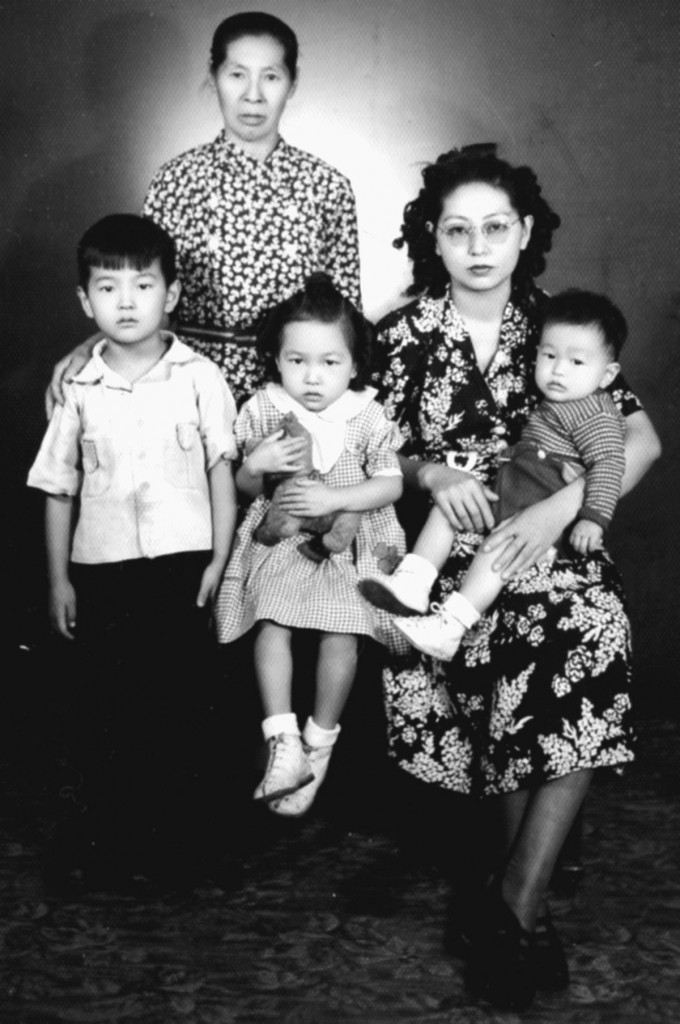

The small number of Japanese immigrants in Mexico by 1942 may obliterate the deep consequences of their eviction from U.S.- Mexico borderlands on the notions of what constitutes a democratic society and the meaning of citizenship. As is the case with the Japanese American community or any other social group whose civil rights were suspended during World War II, the implications of targeting a racialized sector in times of crisis are enormous if principles of equality and freedom are to be held as permanent and universal. Historians of the Japanese diaspora in Mexico believe that the number of Japanese immigrants in the borderlands ranged between 2,700 and 4,700 in 1942. Regardless of their number, the relocation program left all members of the Japanese Mexican community—including those born in Mexico, naturalized citizens, and the Mexican children and wives of Japanese immigrants—without the protection of the Mexican Constitution. [Excerpted from p. 66]

On March 27, 1942, El Paso’s newspapers informed their readers that a group of eighty “Japs” from Juárez would have to leave the border city. If their were any qualms about their uprooting, the newspapers calmed them down, stating that the Japanese Mexicans had “been offered farming land in the prosperous farming community of Santa Rosalía [Camargo], near Chihuahua City, where they will be able to earn a living for the duration of the war.” In fact, the displaced Japanese Mexicans did not stay in Santa Rosalia de Camargo or receive farming land. This group of uprooted borderlanders was held captive in Villa Aldama, Chihuahua. Governor Chavez forced them to work for Tomas Valles de Vivar, a wealthy politician and Chihuahua’s treasurer.

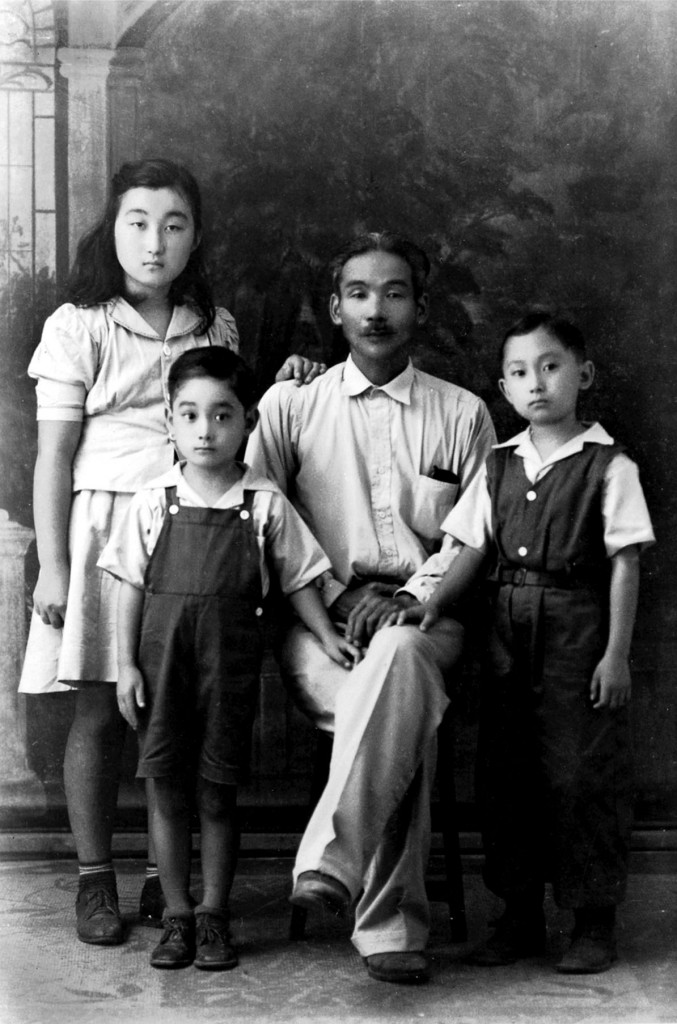

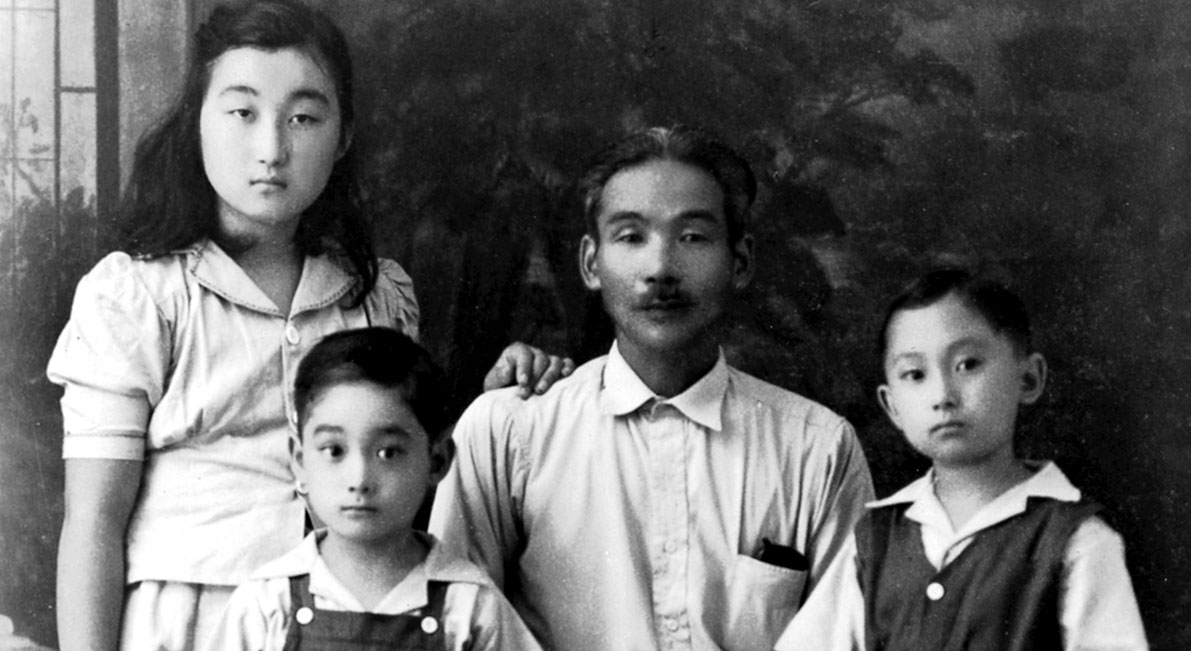

In April 1942, despite their lack of resources to start a new life somewhere else, entire families took the train south of the state of Chihuahua. When allowed, other men chose to leave their children and spouses in Juarez, since their fates and the length of time they would be away from their usual occupations and means of support were unknown. Japanese Mexicans in Juarez were not the first group to evacuate the borderlands. The Mexican army and police in Baja California had already removed Japanese Mexican communities in January 1942 from the North Pacific area adjacent to the United States. By April, only those Mexican Japanese who could not travel to the interior for reasons validated by the Ministry of the Interior (Secretaria de Gobernacion) remained at home.

When military authorities ordered Jesus Kihara to leave his home in Juarez, he did not bring his family with him to Camargo. His Mexican wife and children would fare better in the company of their friends, and they all hoped the period of internment in a concentration camp would end soon. The haste of his travel did not allow him, or the rest of his travel companions, to carry any but the essential items they would need while away from their homes for an unspecified time. Later, uprooted Japanese Mexicans from Juarez would learn that, without appropriate housing, no amount of clothing would be enough to protect their bodies from the weather they endured for several months in Villa Aldama, Chihuahua.

Kihara’s experience is an example of the troubles and tribulations that many Japanese Mexicans had to endure during the relocation program. Kihara and other Japanese Mexican men and women from Juarez arrived in Santa Rosalia de Camargo in the southeast region of the state of Chihuahua at the end of March 1942. Because the Mexican state did not supply the necessary food or clothing for the Japanese Mexican evacuees, the displaced men and women were responsible for acquiring basic supplies to survive during the days they spent in Camargo, a city located approximately seven hundred miles south of Ciudad Juarez. Some Japanese Mexican men managed in only a few days the difficult task of getting a job in the small city to pay for some of their life expenses. Such sources of income disappeared almost immediately, however.

On May 7, Kihara’s group from Juarez, in addition to other, elderly Mexican Japanese individuals from Camargo, was forced to enter the city’s jail. Chihuahua’s governor, Alfredo Chavez, had ordered the incarceration of “nondangerous” civilians in a crowded space for three days “ under the strictest surveillance.” Even though Chavez admitted the innocence of the Japanese Mexican detained, he ordered their arrest. The group of displaced Japanese Mexicans was then escorted out and north of Santa Rosalia de Camargo to the hacienda property of Tomas Valles de Vivar in Villa Aldama. [Excerpted from pp. 84-86]