March 7, 2017

Sara is dedicated to fighting against racial injustice, in part because of her own family’s experience. In summer 2016, she collaborated with others to draft what would become Letters for Black Lives–an intergenerational letter in support of the Black community. According to their website, the project has now expanded to include written, audio, and video translations of the letter in dozens of languages, including multiple dialects of Hmong, Russian, American Sign Language, and Arabic. Onitsuka continues to work with Letters for Black Lives and now oversees college outreach for the initiative.

As a follow-up to previous posts on Japanese American-Black relations and anti-Blackness (here and here), we wanted to learn more about how that history was influencing a new generation of activists. Sara agreed to answer a few questions for us about her commitment to racial justice, and how her family’s incarceration experience inspires her involvement with the Movement for Black Lives today.

How did you get involved in Letters for Black Lives and what’s your role now?

After the deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, I was feeling really frustrated, and I wondered whether there was any action I could take. I found Christina Xu’s tweet asking for help in writing an open letter to our immigrant families addressing anti-blackness (I believe someone I follow had retweeted her). Christina was looking for coordinators, people working on more of the “behind-the-scenes” for the letter, so I DM’ed her on Twitter and that was it! As time went by, I also took on college outreach, which I felt especially passionate about because I’m a student myself.

Have you received any feedback that has helped you to know how the letter has impacted people?

We have a channel called “Highlights” on our Slack team to pass on any success stories and positive responses we received from people. One response that I remember in particular is the NPR interview with Tien Dang and her father. After sending him the letter, her father tells Tien that he is proud of her and to keep fighting for what she believes in. I think that made us all a little teary-eyed.

In an earlier email, you mentioned that combating anti-Blackness in the Asian community is work you hope to continue for your entire life. What makes you feel so passionately about this?

I work towards a world free of White supremacy. One step I can take is combating anti-Blackness in my own community. Throughout history, Black folks have fought for our communities and it is almost as if we expect them to, without us giving back, or in many cases even hurting them (like in the protests over Peter Liang’s conviction). This is not solidarity, and truly, the way Black people have been and continue to be treated should be completely unacceptable to every one of us. Also, Asian Americans are constantly presented as “the good minority” in order to bring down other people of color. Our stereotypes were very conveniently made to be the opposite of Black stereotypes.

Mari Matsuda said it best in her speech “We Will Not Be Used: Are Asian Americans the Racial Bourgeoisie?” to the Asian Law Caucus in 1990: “The role of the racial middle is a critical one. It can reinforce white supremacy if the middle deludes itself into thinking it can be just like White if it tries hard enough. Conversely, the middle can dismantle White supremacy if it refuses to be the middle, if it refuses to buy into racial hierarchy, and if it refuses to abandon communities of Black and Brown people, choosing instead to forge alliances with them.”

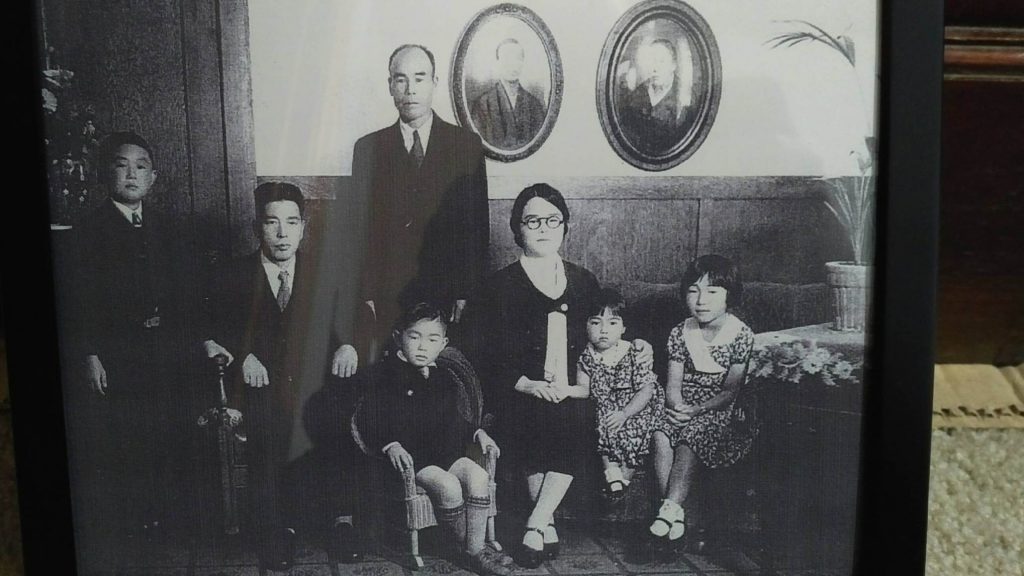

How has knowledge of your grandparents’ WWII incarceration inspired your activism and commitment to social justice today?

Unfortunately, when my grandparents were alive, I didn’t ask them about their time in the camps. I always thought maybe it would be a sensitive topic and they wouldn’t want to discuss it, but I now regret that I didn’t at least try. I think that in a way, not knowing their stories has motivated me to fill in what I can by educating myself, has pushed me to honor their memories by speaking out against the proposed Muslim registry and other acts of injustice, and has made me connect personally with all Japanese American incarceration stories, because my grandparents could have gone through the same thing. So even though I don’t know their stories, just the fact that they suffered in the camps motivates me to keep my family history alive, and to never let it happen again.

Do you have a message for other Yonsei about the importance of racial justice activism?

Japanese American incarceration during WWII might seem distant to us because we weren’t born yet, but we still have so much to fight for. I know it isn’t necessarily in the Japanese culture to take up a lot of space, but we need to use our voices and speak up when something is wrong. Though our families have been in America for generations, remember that we are still seen as, and treated like, outsiders in America.

—

Sara Onitsuka is a student at The College of Wooster; follow her at @saraiume. She was interviewed by Densho Communications and Public Engagement Manager Natasha Varner.

[Header photo: Sara Onitsuka (bottom row, second from right) with friends standing up against police brutality while studying abroad in Copenhagen during Fall 2016. Photo courtesy of Sara Onitsuka.]