August 28, 2019

Guest post by Eric Muller, Dan K. Moore Distinguished Professor, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

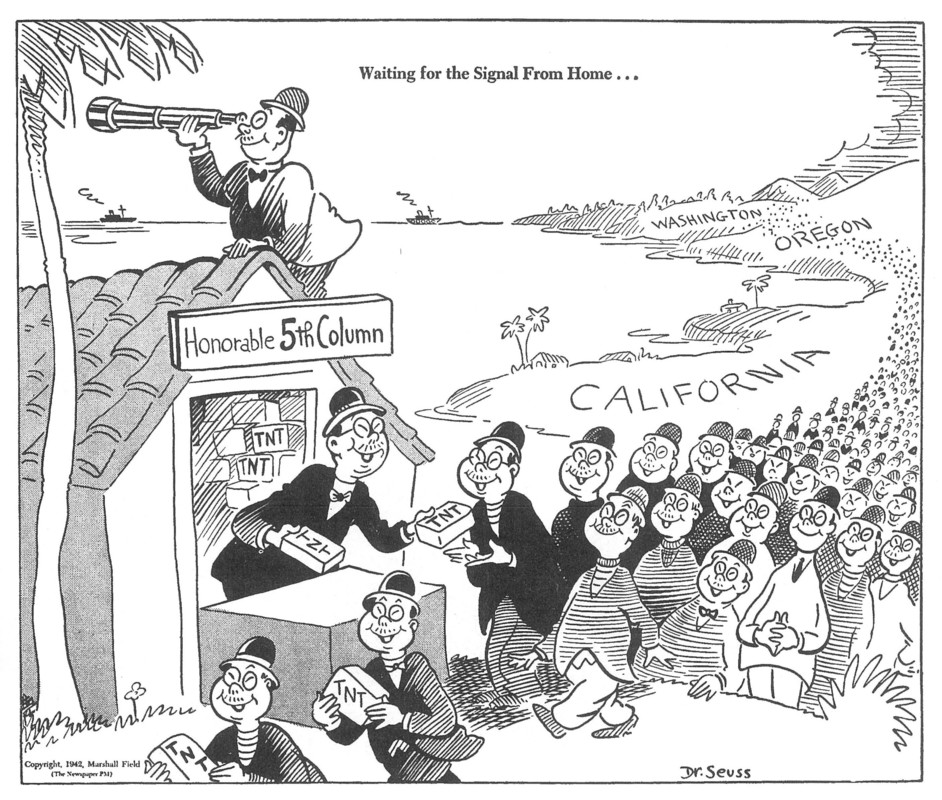

Cambridge University Press recently published Roger W. Lotchin’s Japanese American Relocation in World War II: A Reconsideration. The book’s goal is to correct what the author characterizes as several ubiquitous and mistaken findings in the literature on the removal and confinement of people of Japanese ancestry in World War II (hereinafter “Japanese removal”). The most important of the findings that Lotchin seeks to “correct” is that racism was a key cause of the removal, though ample historical evidence attests that indeed it was.

A number of critical reviews of the book have begun to appear. They are doing important work. They are condemning its crabbed definition of racism as a belief in the biological inferiority of a racial group. They are pointing out how it mischaracterizes, caricatures, and sometimes ignores the voluminous literature it purports to be refuting. They are identifying deficiencies in its source material and highlighting its credulity toward sources that deserve skepticism.

I believe the problems run even deeper. The book is undone by a rudimentary error about causation and by the omission of crucial evidence.

The book’s thesis is simple to state. According to Lotchin, racism was not a significant cause of Japanese removal because before Pearl Harbor, racism against the Japanese was on its way to extinction and Japanese Americans were far along the path of assimilation. If Japan had never made war against the United States, Japanese Americans would have continued along this path. So it was Pearl Harbor, not racism, that rerouted them to Manzanar and the other camps. National security concerns, not racism, caused Japanese American removal.

This is not how causation works. The fact that something has receded does not prevent it from reemerging and causing something. Think of epilepsy. A young person has a number of seizures and eventually finds medicine that controls them. Over time, medical advances keep him seizure-free. Then the person has an entirely sleepless night because his upstairs neighbor is playing loud polka music. At dawn, the person has an exhaustion-induced seizure.

What caused it? Lotchin would say the loud polka music did. The person’s epilepsy had abated; had it not been for the polka-induced wakefulness, he would have continued to enjoy good health. The polka music was the culprit. But that’s nonsense. Epilepsy was the culprit. The polka music simply created the conditions for its reemergence.

Assimilation and the abatement of old hatreds did not protect German Jews from the return of anti-Semitism in the early 1930s. It was anti-Semitism that caused the boycott of Jewish-owned businesses in Germany in April of 1933, not the Treaty of Versailles or the chaos of the late Weimar period that brought the Nazis to power.

Lotchin’s book offers us no reason to think otherwise about Japanese removal. That Japanese Americans gained an increasing measure of acceptance across the 1930s does not prove that racism could not be a significant cause of their uprooting in the wake of Pearl Harbor.

The book does not rest its analysis entirely on the supposed death of anti-Japanese sentiment. Lotchin also reviews key historical records for evidence of racism – the biologically defined kind, which is the only kind he will acknowledge – and doesn’t find any.

This is odd, because that evidence stands in plain sight in the key government record.

Early in 1943, the Army general who had ordered mass removal of Japanese Americans from the coast and overseen their initial detention in 1942 prepared a report documenting and explaining his actions and orders. The report is the most direct and comprehensive official statement of the rationale for Japanese removal. It said this:

“In the war in which we are now engaged racial affinities are not severed by migration. The Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on United States soil, possessed of United States citizenship, have become ‘Americanized,’ the racial strains are undiluted.”

A “strain” is a genetic variant of a microorganism: a “strain” of bacteria, a “strain” of the flu. Would it be possible to cast the transmission of “racial affinities” across generations in a more biological way? I can’t imagine one.

How does the book explain away this language explicitly grounding Japanese removal in biological racism? It doesn’t, because it doesn’t mention the passage at all. Lotchin analyzes other paragraphs from the same report. Indeed, he carefully examines passages adjacent to the one about the “undiluted racial strains.” But he omits that language entirely. Indeed, he goes further, flatly asserting that the report “did not speak of biology.” (101)

The omission matters a great deal. This language apart, the best evidence that racism was an important cause of Japanese removal is the differential treatment of American citizens of Japanese ancestry on the one hand and of German and Italian ancestry on the other. The government arrested all people of Japanese ancestry, citizens and aliens alike, as well as certain identified German and Italian aliens, but issued no mass arrest orders against American citizens of German or Italian ancestry. Suspicion leapt across generational lines from Japanese alien parents to their citizen children, but not from German and Italian alien parents to their citizen children. What was it that made only Japanese American citizens as suspect as their parents? The very thing Lotchin says he looks for but cannot find: the supposed “racial strains” in the Japanese body.

So the book’s thesis about the insignificance of racism is marred by a basic error about causation and by the inexplicable omission of key evidence. These are not quibbles. They are gaping holes at the core of the book’s argument.

No scholarly consensus is immune from revision. That includes the consensus that racism was a significant cause of Japanese removal. But distorting causation and omitting evidence is not how responsible revision is done. How the book survived the peer review process of a prestigious university press is quite a puzzle.

—

Guest post by Eric Muller, Dan K. Moore Distinguished Professor, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Muller is the author of Free to Die for their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II and American Inquisition: The Hunt for Japanese American Disloyalty in World War II and editor of Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II. He’s the creator of the podcast Scapegoat Cities, which tells as-yet-untold stories of Japanese Americans’ experiences of removal, imprisonment, and efforts at obtaining compensation after the war. He’s at work on a new book about the lawyers who helped to run the War Relocation Authority’s concentration camps for Japanese Americans.