May 5, 2021

The resistance of nearly 300 young men who refused to be drafted into the U.S. military out of U.S. concentration camps has become a prominent part of the Japanese American WWII incarceration story. Maligned as disloyal troublemakers for decades after the war, members of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee and other draft resisters are rightfully recognized as civil rights heroes today. But there is an equally inspiring — and largely forgotten — story about hundreds of Issei mothers who also protested the draft from within the camps.

Contrary to commonly-held stereotypes about good wives and wise mothers with small voices and few opinions, Issei mothers were no strangers to resistance. Prior to WWII, Japanese immigrant women created shelters and organized services for picture brides escaping abusive marriages, sustained worker strikes with the invisible labor of feeding a movement, and in at least one case, organized to demand paid maternity leave.[1] That these women were fully capable of holding their own will come as little surprise to anyone with a Japanese grandmother.

In Minidoka in January 1944, a strike by some 160 boilermen and janitors — over recent layoffs and the imposition of a new 24-hour work schedule — left the camp without hot water in the middle of the harsh Idaho winter. On January 6, a delegation of seventy-five Issei and Nisei women marched on the offices of Assistant Project Director R.S. Davidson and effectively held an eight-hour sit-in to push camp administrators to meet the striking workers’ demands. They refused to leave until he forwarded a statement from the women to War Relocation Authority (WRA) Director Dillon Myer not asking but demanding the restoration of hot water:

“We, the women and mothers of this project, demand hot water service at once. We have been without hot water for two days due to dispute [sic] between administration and workers…. Many of us have sons, husbands, and brothers in the armed forces doing their share for this country and yet we have to go through these hardships when a little effort on your part may straighten out this uncomfortable situation in which we are only victims of circumstances. Give this matter your immediate attention and wire back at once so that we can have hot water immediately.”[2]

The letter from the “Ladies of Hunt Relocation Center” would prove to be a precursor to continued attempts by Issei women to demand change in WWII concentration camps.

The following month, in February 1944, a group of Issei women calling themselves the Mothers’ Society of Minidoka came together to petition the government against drafting their American-born sons out of the camp. As Mira Shimabukuro notes in Relocating Authority: Japanese Americans Writing to Redress Mass Incarceration, the women’s petition preceded more well-known statements from male-led groups like the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee — which, she suggests, means that the first coordinated, public resistance to the draft came not from citizen men but from immigrant women who were barred from naturalization.

According to James Sakoda, a researcher for the Japanese Evacuation and Resettlement Study, the women had been disappointed that draft-age men in the camp had not yet mounted an organized protest, and decided to write a petition leveraging their position as mothers of American citizens. This is not to say that Nisei men did not protest the draft in Minidoka. Draft-age men began holding their own meetings in early February, and a petition calling for “the restoration of every right and privilege of American citizenship” was circulated in several blocks — but few were willing to sign it and the Nisei petition soon “died a natural death for lack of support.”[3]

The Mothers’ Society enlisted the help of Nisei lawyer Minoru Yasui, who had been “released” to Minidoka after losing his Supreme Court challenge. Yasui completed a draft of the petition on February 12, but many of the women complained that it was “too weakly worded,” painted the mothers as overly emotional, and only addressed the segregation of Japanese American soldiers but not the larger issue of their children’s citizenship. Undeterred, they began to hold secret meetings where they took it upon themselves to write another, stronger version.

The women assigned three representatives to rewrite the petition: a Mrs. Miyata, who had been transferred to Minidoka from Tule Lake with her draft-age Nisei son; Mrs. Takagi, a graduate of a girls’ college in Japan; and Mrs. Washisu, who had also attended college in Japan and was a driving force behind the earlier Nisei petition.[4] Their revised letter explicitly named the injustice and hypocrisy of the forced removal, and called for an end to the draft of Japanese American men from the camps until their rights as U.S. citizens were restored:

“[O]n the Pacific Coast with the so-called ‘military necessity’ as a reason the foundation of our life, the fruit of several decades of toil and suffering, was completely overturned; and first generation aliens and even Nisei—who are American citizens—were forced to lead a life within barbed-wire fences…. We understand that the purpose for which the United States is allowing tremendous sacrifices in fighting the war today is to establish ‘freedom and equality’ throughout the world. When they, the Nisei, consider the purpose of this war and then think about the treatment they are receiving at present, they discover the existence of a great paradox…. To think of sending them in this condition to the front, we, as mothers, considering the past and the future, feel an extreme and unbearable anguish.

“… In this connection we would like to have you please consider the suspension of the drafting of citizens of Japanese ancestry until they regain the confidence that they can demonstrate their loyalty to the United States from the bottom of their hearts as formerly.”[5]

The petition was signed by 100 women and sent to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt as well as President Roosevelt, WRA Director Dillon Myer, Minidoka Project Director Harry L. Stafford, and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson on February 20, 1944.

Similar letter-writing campaigns led by Issei mothers in other camps soon followed. In Amache, the Blue Star Mothers and Women’s Federation filed a joint resolution calling for the restoration of Nisei citizenship rights as a necessary precondition to reinstate the draft for incarcerated Japanese Americans. Over 100 members of the Poston Women’s Club signed a petition requesting to delay the induction of their sons and brothers on the grounds that they were needed to help their families resettle outside the camps.[6]

The largest campaign took place in Topaz, as detailed by Cherstin Lyon in Prisons and Patriots: Japanese American Wartime Citizenship, Civil Disobedience, and Historical Memory. Mothers formed an organizing committee with two representatives from each block and, after some debate over whether or not to issue an ultimatum withholding their sons’ military service unless their full rights as citizens were restored, drafted a petition protesting the “discriminatory measures directed against them,” in early March 1944.

The Mothers of Topaz specifically called for an end to the racial segregation of Japanese American soldiers, “desir[ing] for our sons the privilege of entering the branch of the armed forces which they select and of receiving full benefits accorded American citizens.” But they also took the opportunity to sharply criticize the forced removal and incarceration of U.S. citizens:

“When the amicable relationship that existed between America and Japan for the last eighty years was broken by the declaration of war, most of us being aliens, we understood why our rights and privileges were curtailed. But we cannot understand why our children who are American citizens were placed in the similar category as we ourselves. We mothers deeply regret this action on the part of the Government, which by its unexpectedness caused immeasurable psychological suffering in our children.”[7]

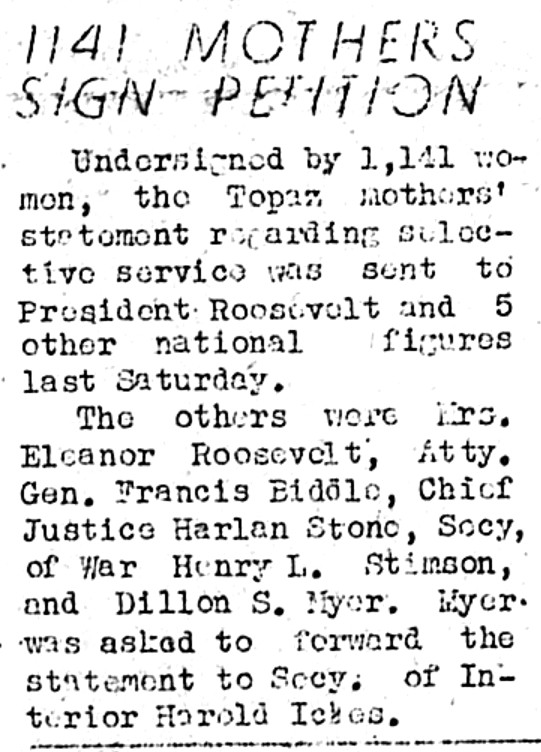

An impressive 1,141 women ultimately signed the petition, which was sent to the President and other high level government officials on March 11, 1944.

The responses to these incarcerated Issei mothers (from those who even took the time to respond) ranged from curt to patronizing to vaguely threatening. The First Lady was the only person to respond to the Mothers’ Society of Minidoka petition — in a hurried letter dictated to a secretary because “Mrs. Roosevelt had to leave before signing.” The Mothers of Topaz received three replies: one from Acting WRA Director Leland Barrows assuring the women that “many responsible officials” were giving the matter their “thoughtful attention,” another from Brigadier General Henry L. Dunlop informing them that they had no authority to dictate War Department policy to assign inductees wherever they were “most useful to the prosecution of the war,” and a third from Dillon Myer that simultaneously thanked the mothers for their “devotion… to the democratic principles” and warned them against “indicating reluctance to contribute to the winning of the war.”[8]

Even though the petitions didn’t stop their sons from being drafted, it was a powerful display of Issei women’s ability to organize, make their voices heard, and write their own narrative as leaders within their communities who would not accept abuse without complaint. Their efforts — which are all the more remarkable because of their precarious position as “enemy aliens” — add a fascinating chapter to the history of American draft resistance that deserves to be remembered and celebrated today.

—

By Nina Wallace, Densho Communications Coordinator

For more information, see Cherstin Lyon’s Densho Encyclopedia article on the Mothers of Topaz and “Another Earnest Petition: ReWriting Mothers of Minidoka” in Relocating Authority: Japanese Americans Writing to Redress Mass Incarceration by Mira Shimabukuro.

[1] During the Oʻahu sugar strike of 1920, Japanese women laborers demanded eight weeks of paid maternity leave. (Edward Beechart, Working in Hawaiʻi: A Labor History; Gail Nomura, “Issei Working Women in Hawaiʻi” in Making Waves: An Anthology of Writings By and About Asian American Women.)

[2] Letter from “Ladies of Hunt Relocation Center” to Dillon Myer, January 6, 1944. (Included in War Relocation Authority report on the “Boilermen’s Situation” in Minidoka, 1943-1944.)

[3] James Sakoda, “Nisei Draft,” April 15, 1944 (61-65, 71-77).

[4] It’s likely that the names ascribed to the three Mothers’ Society of Minidoka representatives in Sakoda’s report are pseudonyms.

[5] Letter from the Mothers’ Society of Minidoka to Eleanor Roosevelt, February 20, 1944.

[6] Lyon, 129; Shimabukuro, 137, 169.

[7] “Statement from Mothers of Topaz, W.R.A. Center,” March 11, 1944.

[8] “Three Answers to Mothers’ Petition Here,” The Topaz Times, April 12, 1944.

[Header photo: An Issei mother and her son in U.S. Army uniform, standing in the family’s strawberry field in Florin, California prior to forced removal. May 11, 1942. Photo by Dorothea Lange, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]