June 8, 2017

It didn’t take long for hatemongers to pounce on these tragedies as an opportunity to demonize and punish Muslims. Katie Hopkins—who has created a name for herself by making fun of fat people, shaming poor kids, and referring to refugees as “cockroaches” who deserve to die at sea—came out swinging, demanding a “final solution” against Muslims. Tariq Ghaffur, formerly a police chief and assistant commissioner at Scotland Yard, called for the detention of “jihadis” in a “special centre” where they would be “risk-assessed and theologically examined” as part of a mandatory deradicalization program. On the other side of the pond, our own president took to Twitter to renew his support for what he is now unabashedly calling a travel ban.

https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/871674214356484096

https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/871677472202477568

Fox & Friends then fanned the flames on Sunday, lending their very public platform to Hopkins and former UKIP leader Nigel Farage, who both expressed explicit support for the internment of 23,000 “known terrorists” and “persons of interest.” The following day, talk show host Michael Savage, who credits himself with helping get Donald Trump into the White House, asked why “Islamists” on government watchlists were not being interned “before they run people over on a bridge or stab people on the streets.” Because that was apparently not inflammatory enough, he went on to suggest that “the internment in World War II” may have helped the U.S. win the war.

Varying degrees of condemnation were quick to follow, from Fox & Friends host Clayton Morris’ tepid post-interview clarification that the network finds the “idea” of internment “reprehensible” to a strongly-worded article from Shaun King rightfully attributing these calls to bigotry, not safety.

While it’s heartening to see these public disavowals—something we did not see when Japanese Americans were being targeted seventy-five years ago—there seems to be some confusion about what exactly we are disavowing.

Calls for detaining Muslims, in the U.K. and here at home, have been almost exclusively expressed in terms of internment, yet most of the outrage has equated this to the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Now, make no mistake: when pundits and politicians start talking about rounding up residents of their country based solely on race or religion, that connection exists and we must say so, loudly and repeatedly. But spreading misinformation, even with the best of intentions, helps no one.

The persistence of euphemisms like “internment camps” and “relocation centers” to describe the concentration camps where most Japanese Americans were sent after being removed from the West Coast is partly to blame. But we’re not here to talk semantics. The problem with saying “internment” when we’re really discussing a systematic exile based on race is much deeper than that. By focusing solely on the experiences of Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II, we risk erasing those were interned—whose stories bear much more in common with Muslims being targeted today.

There’s a reason Japanese Americans, and scholars of our history, have been trying for decades to establish “incarceration” as the preferred term for what happened during WWII. “Internment” refers to the detention of enemy aliens during time of war. It is, for better or for worse, legally permissible under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 and was used during both World Wars to confine German, Italian and Japanese immigrants. It is inaccurate and misleading to apply it to Japanese Americans forcibly removed from their homes as a result of Executive Order 9066—of which two-thirds were U.S. citizens and the remainder were barred from obtaining citizenship by racist naturalization laws.

Some 9,000 Japanese Americans—mostly Issei men but also some women, Kibei and Nisei—were subject to internment during WWII. Previously identified as potentially dangerous and placed on a government watchlist, these arrests began mere hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor. After being taken into FBI custody and held for several days or weeks in local jails and immigration stations, detainees were transferred to internment camps run by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, where they received hearings to determine their fate.

On the surface, this may sound reasonable, fair even. But when we dig deeper into the historical record, the racial animosity and rights violations that plagued the WWII internment program become clear. The intelligence agencies that compiled the so-called “custodial detention list” relied on biased assumptions to determine a threat, blacklisting individuals based on membership in Japanese cultural organizations, positions as Shinto priests or Japanese language school instructors, and ties to relatives in Japan. Alien Enemy Hearing Boards made their decisions based in part on an internee’s religion and perceived attitudes toward America. These kangaroo court hearings typically lasted just 20-30 minutes, and internees were not allowed to have a lawyer present or challenge the evidence presented against them.

When Donald Trump cited “what FDR did many years ago” to justify proposed restrictions on Muslim Americans during his presidential campaign, this is the precedent he referred to. When Nigel Farage says action must be taken against people whose names appear on a “known terrorist list,” this is the relevant history.

Internment and incarceration, though they rise from the same hysteric and xenophobic impulses, are not interchangeable. Conflating the unconstitutional incarceration of citizens with the detention of immigrants during a war obscures historical facts and muddies the water in our current discussions. We must be clear on these facts to understand what happened in our past and what we face in the present. We are not at war with Islam. Our Muslim friends and neighbors are not “enemy aliens.” Racially profiling an entire group of immigrants as potential terrorists is no less abhorrent than imprisoning innocent citizens.

Public acceptance of race-based internment paved the way for the much more drastic step of race-based mass removal. If we wish to prevent a repeat of WWII incarceration, then we must first prevent a repeat of the abuses of WWII internment.

—

By Densho Communications Coordinator Nina Wallace

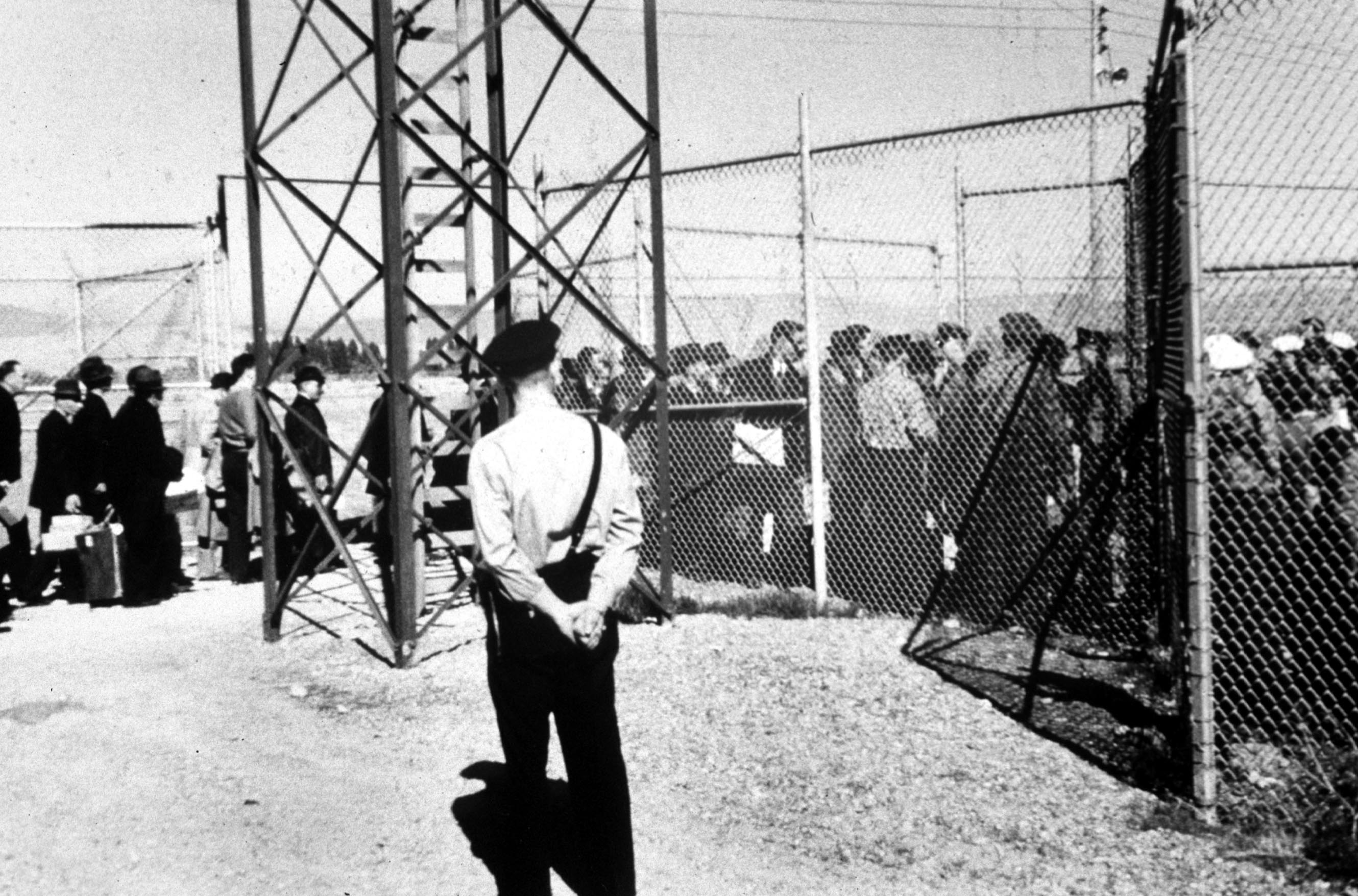

[Header photo: New arrivals at the Department of Justice internment camp at Fort Missoula, Montana, c. 1942. Photo courtesy of the K. Ross Toole Archives, University of Montana at Missoula.]