May 16, 2017

Though it is a memoir, Arakawa changes the names of all the people in it, including her own. She writes in the first person voice of Shizuye Mitsui—dubbed “Marie” by a well-meaning teacher—who ages from nine to thirteen over the course of the war. One of two children, her parents own a successful cleaning business in San Francisco when the war comes. Marie’s story takes us through the anxieties of the period after December 7 to their incarceration at the Stockton Assembly Center and at the Rohwer, Arkansas concentration camp. The family “resettles” in Denver as the war draws to an end.

The core of the book centers on the incarceration, but Arakawa spends a good deal of time on both her prewar life in San Francisco and the period after they left camp. Her family lives initially in the Polk District, but moves to a bigger shop in the Sunset District in December of 1940. Marie soon finds that the new area is less friendly to Japanese Americans. The family is hemmed in by restrictive covenants, while Marie dodges bullies and hecklers at school.

The postwar chapters are among the most heartfelt. In Denver, the family lives in a shabby residential hotel with a single bathroom shared by a whole floor. While her parents have good jobs, they are constantly fighting, and Marie struggles mightily in a hostile school environment with no friends. She even contemplates suicide, when her life is saved by the appearance of an old acquaintance from Rohwer who introduces her to other Nisei in Denver. It is a harrowing portrait of the difficulties of the immediate postwar period.

The wartime sections cover familiar territory, but from the somewhat unusual perspective of a “tween.” Marie is a canny observer, sometimes of things she doesn’t quite understand, reminding the reader of some of the unreliable narrators of classic Hisaye Yamamoto stories. Because she is writing as a child, the crises here are things like her father’s drinking and sake brewing in camp or efforts to keep possession of a prized coat through all the turmoil, as opposed to the usual stuff around the “loyalty questionnaire” or military service—a refreshing approach.

There are a couple of unusual elements to her family’s story as well. In the weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, two FBI agents move into their home and hold them under house arrest, something I’ve never heard of before. After about a week, they are cleared and the men move out. Later, the family decides to “voluntarily” move to Stockton, where her maternal grandparents run a hotel, hoping to avoid incarceration, as some 10,000 other Japanese Americans did. As was the case for half of them, this proved to be of no avail, and they were forcibly removed from Stockton after two months anyway.

Through the near constant moving, Marie and her family struggle to adjust time after time to new surroundings and situations. Friends and acquaintances come and go continually throughout the book, something that I first found trying but eventually came to realize is a crucial part of the story. The Mitsuis endure and survive. One is left hopeful as they return to San Francisco from Denver, confident that they will endure and survive once more.

An afterword includes an account of how Arakawa began to take an interest in writing in her 60s and how the book came to be.

As has been the trend with more recent memoirs, this one is angrier and more frank than earlier works such as Monica Sone‘s Nisei Daughter, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James Houston’s Farewell to Manzanar, and Yoshiko Uchida‘s Desert Exile, probably the three most widely read camp-centered memoirs. The Little Exile is also much more detailed in its observations and numerous in its stories, which some readers might find a bit tedious, even if the stories are mostly well told.

Each Nisei memoir is precious and adds its own contribution to our collective knowledge of the incarceration period. Arakawa’s detailed child’s eye view of that story is by turns funny, angry, and sad, like most children are. It is a worthwhile addition to the camp memoir club.

—

Audience: This book was not written specifically for a YA audience but the content is appropriate for that age group and up.

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

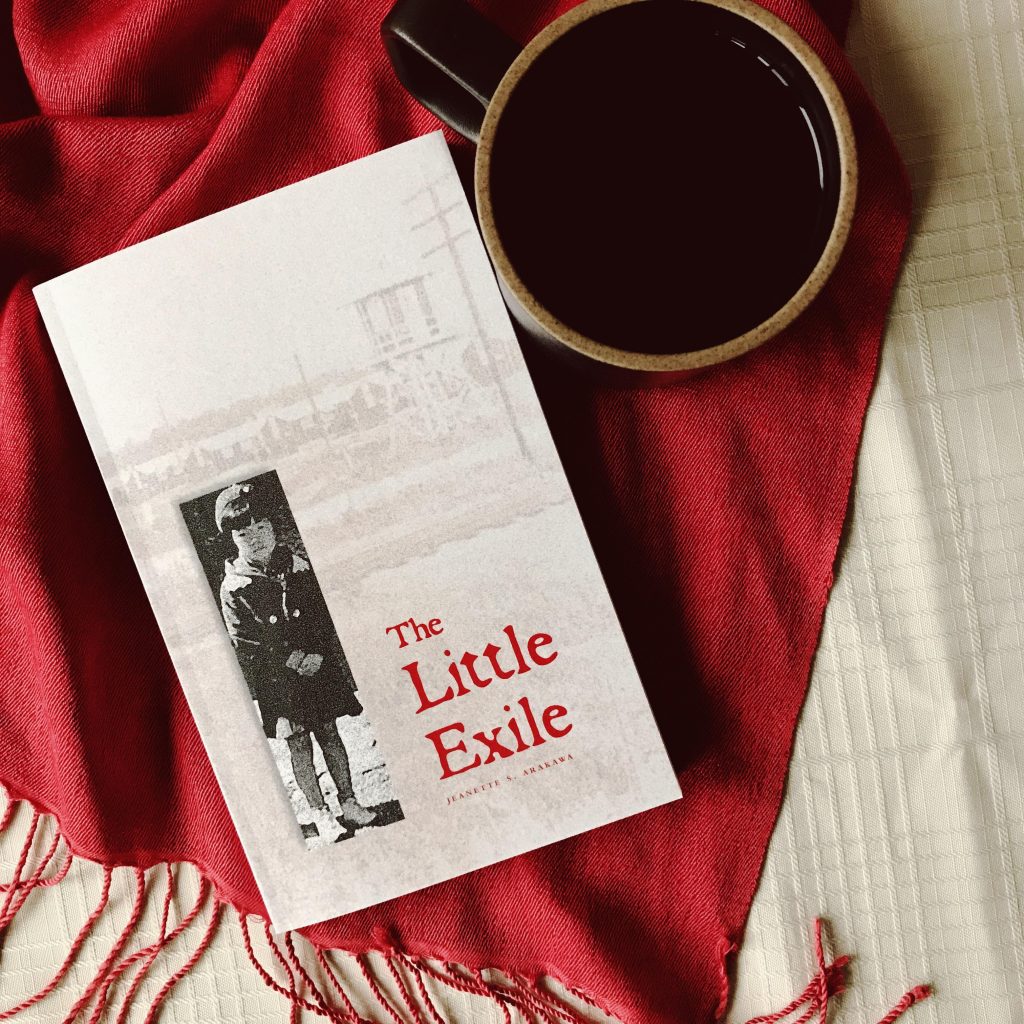

[Header photo: Girl posing in front of barracks and Heart Mountain. May 12, 1944. Photo courtesy of Yoshio Okumoto.]