July 14, 2021

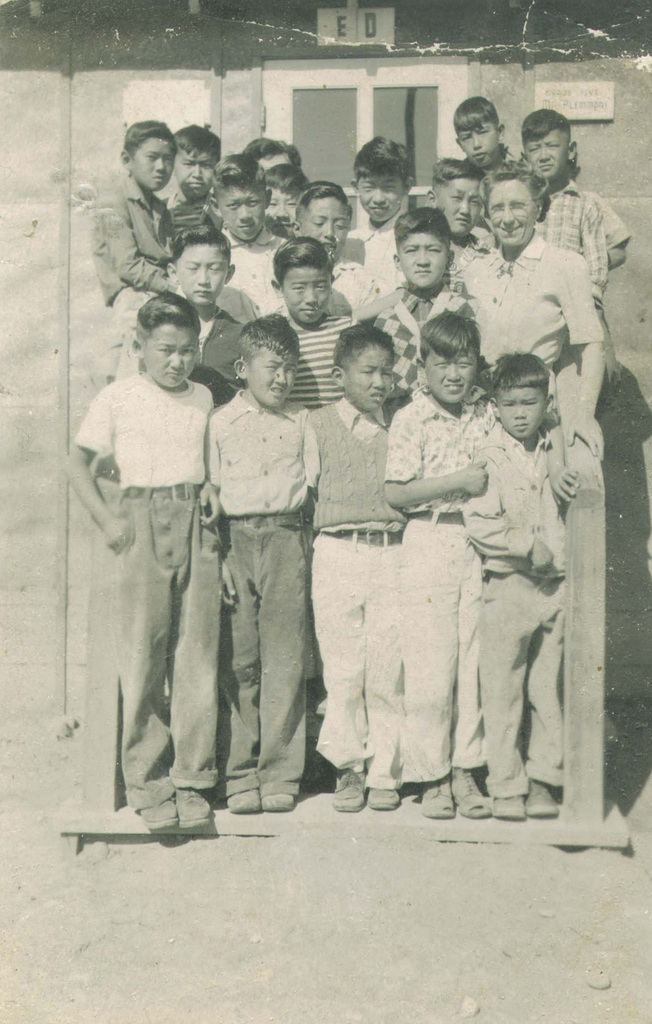

Joe Yasutake was only nine years old when his father was apprehended by the FBI and interned as an enemy alien. In a matter of hours following the attack on Pearl Harbor, his peaceful Seattle childhood was replaced with family separation, forced removal, and life inside a series of detention facilities and concentration camps.

Years later, he recalled this time in his life during an oral history interview with Densho:

“Each movement seemed to kind of last over an academic year….the fourth grade ended in about February or whenever it was that we, we were hauled off to Puyallup, and then I was moved…to the fifth grade in Minidoka. And I’m almost certain I finished the fifth grade in Minidoka before, and I think it was over the summer or early fall that we went to Crystal City. And the same thing with when we moved from Crystal City.”

Without having lived through that experience, it’s difficult to fathom such an extreme disruption to our daily lives. Sites of Shame, an innovative new mapping tool from Densho, allows viewers a fuller picture of what those chaotic years looked like for the Yasutake family and thousands of others.

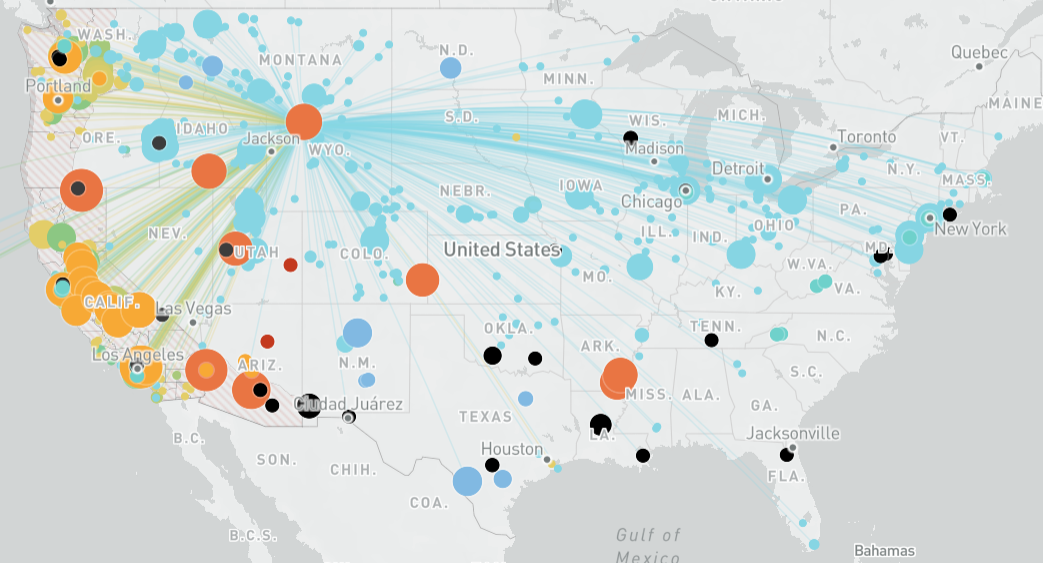

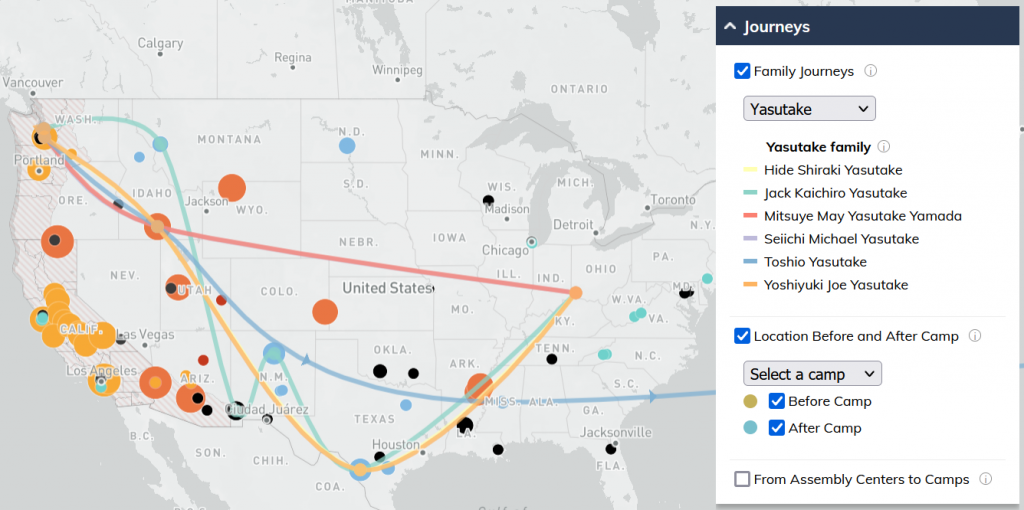

The site maps out the journey of the Yasutakes and a handful of families from their pre-war homes in mostly West Coast cities, to detention facilities, then concentration camps, and finally their dispersal to post-camp homes scattered across the US. It also allows users to call up lines that trace the paths of some 120,000 Japanese Americans as they were forced from their homes into camps.

“I think the data visualization element is really helpful in conveying some types of information,” says Densho Content Director Brian Niiya, a co-creator of the new Sites of Shame. “I’m particularly intrigued by the visualizations of the journeys to and from the WRA camps, for instance. It really gives the user a picture of where a camp’s inmate population came from and where it went to, and allows for quick visual comparisons between camps.”

Sites of Shame is a revamped version of an earlier map published by Densho in 2005. Using the latest scholarship on WWII incarceration history, data gathered by the US government during WWII, and original research by the Densho team, the new site maps out nearly 100 sites where Japanese Americans were detained.

Joe’s sister, the poet Mitsuye Yamada, says she feels honored to have her family’s story included:

“I know that [my parents], Jack and Hide Yasutake, are up there bursting with pride that their family story has been immortalized in this way by the incomparable Densho team. I am happy that our family history lives on and that other Nikkei who also have similar stories will be inspired by reading our story and will add their own family histories to this rich archive. There must be many more stories out there!”

The new site also has special meaning for one of the site’s co-creators, Densho’s content director Brian Niiya.

“Two of the sites added—the Grove Park Inn in Asheville, North Carolina and the Assembly Inn in Montreat, North Carolina—have special meaning for me, since my mother and her family were among the Japanese Americans from Hawai`i who were held there from 1942-43. While there has been prior scholarship on these and a couple of other similar camps, there had been no mention of the Hawai`i families of Issei internees like my mom’s until new research by Heidi Kim of the University of North Carolina.” Kim’s new Densho Encyclopedia articles on these two sites are among the dozens of new or updated articles on the various sites that have been added as a part of the project.

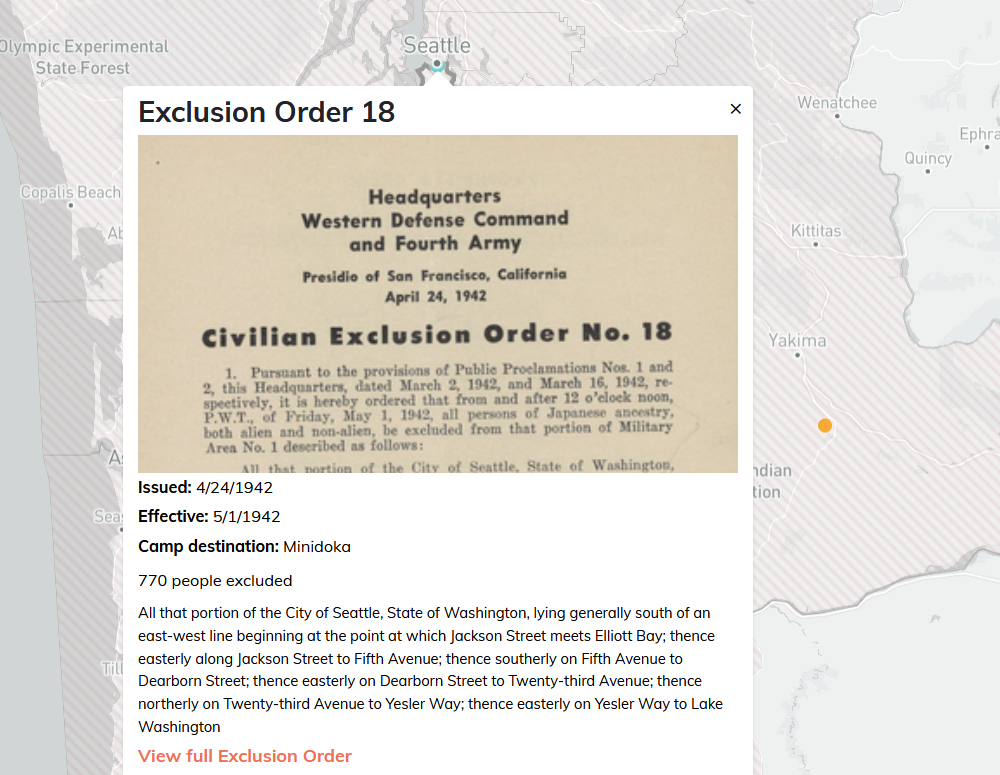

The new Sites of Shame also marks the first time that anyone has mapped all 108 civilian exclusion orders. Users can see the exact exclusion order that called for the removal of their family or neighbors during WWII, and then follow their journey from their homes to the various detention sites.

Asked about the project, Densho’s technology director and Sites of Shame co-creator, Geoff Froh added, “Beyond all of the amazing content, the exciting thing to me is that Sites of Shame was developed with open-source tools, and designed to be a flexible platform. This means that we can build all kinds of other applications using what we’ve learned from the project. Look for interesting new data visualizations and mapping features in the near future!”

The creators of the site emphasize that it is a living document that will be updated as new information comes available. There is still much about WWII incarceration history to be discovered and the Densho team is committed to updating resources like Sites of Shame so that it remains relevant and up-to-date for years to come. There are also plans in the works to add resources for educators and students. But for those with family connections to Japanese American and to general history enthusiasts, the site is ready to go.

“I am hopeful that anyone with a familial connection to the incarceration will be inspired to start exploring the site to retrace their own family’s journeys, and in so doing, will learn some new things and come away with many more questions whose answers may or may not lie elsewhere in our website,” remarks Brian Niiya.

—

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communications and Public Engagement Director