March 2, 2020

The name Miller Freeman has been in the news this past week after a Day of Remembrance installation at Bellevue College by artist Erin Shigaki was defaced by a school administrator. Shigaki’s art installation, “Never Again Is Now,” depicts two Japanese American children in a WWII concentration camp, and an accompanying artist statement described the impact and ongoing legacy of Japanese American incarceration.

A vice president responsible for fundraising used White-Out to erase the following sentence:

After decades of anti-Japanese agitation, led by Eastside businessman Miller Freeman and others, the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans included the 60 families (300 individuals) who farmed Bellevue.

This is not the first time people have tried to protect the memory of Miller Freeman. This past fall a similar line was struck from Shigaki’s work when it appeared at the City of Bellevue’s Bellwether Festival. Dr. Ron Magden, while doing research on Japanese American history, discovered that papers and letters documenting Freeman’s anti-Japanese writings were removed from the University of Washington archives. Also, Professor Roger Daniels, the nationally acclaimed history expert, did a Seattle TV news segment about Miller Freeman’s anti-Japanese actions, and this news story was never shown.

Why are people trying to protect the memory of Miller Freeman?

Miller Freeman was a visionary founding father of modern Bellevue; a civic leader who championed the building of a two-mile floating bridge that provided a fast connection between Bellevue and Seattle; and a business leader who, with his son, established Bellevue Square – the first suburban shopping mall in the Pacific Northwest.

However, there is another side to Miller Freeman. The business mogul held deep-seated racist beliefs about Japanese Americans and, as Bellevue’s Japanese population grew throughout the early 1900s, so too did Freeman’s agitation against the community. The book Strawberry Days: How Internment Destroyed a Japanese American Community and a recent article by David Neiwart document these beliefs, including this quote from an op-ed by Freeman:

“The Japanese cannot be assimilated. Once a Japanese, always a Japanese. Our mixed marriages — failures all — prove this. ‘East is East, and West is West, and ne’er the twain shall meet.’ Oil and water do not mix.”

Because of Freeman’s standing with business, political, and government leaders; he was in a position of power that enabled him to do great harm with those beliefs. As Neiwart illustrates, Freeman’s anti-Japanese racism materialized in his role as a champion of Washington State’s Alien Land Laws that prohibited Japanese from owning land, the founder of Washington’s Anti-Japanese League, and a vocal spokesperson for the removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast and preventing Japanese Americans from returning to Bellevue after the war.

Members of the Bellevue Japanese American community knew this side of Miller Freeman, as seen in an oral history interview Densho did with Sumie Suguro Akizuki in 2008.

“Every person that you would talk to of the Nikkei community would know that Miller Freeman was anti-Japanese,” Akizuki recalled.

It is hard to hear when our leaders have such problematic pasts. But as America wrestles with race relations and understanding the influence of power on our communities, it is important for us to remember that economic self-interest and racial animosity have historically been used to scapegoat and blame individuals, families, and communities who fall outside the norms of what those in power deem to be “acceptable” American behavior.

As Erin Shigaki wrote in the description of her work, “May we be reminded that America’s racial policies have always had many economic motives and beneficiaries.”

Ironically, Bellevue College tried to hide Miller Freeman’s anti-Japanese actions during the commemoration of the Day of Remembrance, a time for us to remember and vow never to forget the history and lessons of the WWII Japanese American incarceration. One of the lessons of the Japanese American incarceration is the corrosive nature of power, and how vulnerable immigrants and communities of color are easily demonized and blamed for economic hardship and other community problems. During WWII, the West Coast Japanese American community was scapegoated as a dangerous national security risk, and that false argument was laid upon decades of racial animosity led by Miller Freeman and others.

One of the silver linings of the Japanese American incarceration and its aftermath was to experience humankind’s capacity for reconciliation. Starting in the early 1980s, the U.S. Government carried out an in-depth process of listening to and learning from the Japanese American community, culminating in the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. By talking about what really happened and the ugly truth of this history, healing was allowed to happen.

In attempts to whitewash the ugly parts of history, the actions of Bellevue College administrators have resulted in this history being more widely known. We hope these heinous actions ultimately lead to more healing — and to more accountability — too.

—

By Densho Director Tom Ikeda

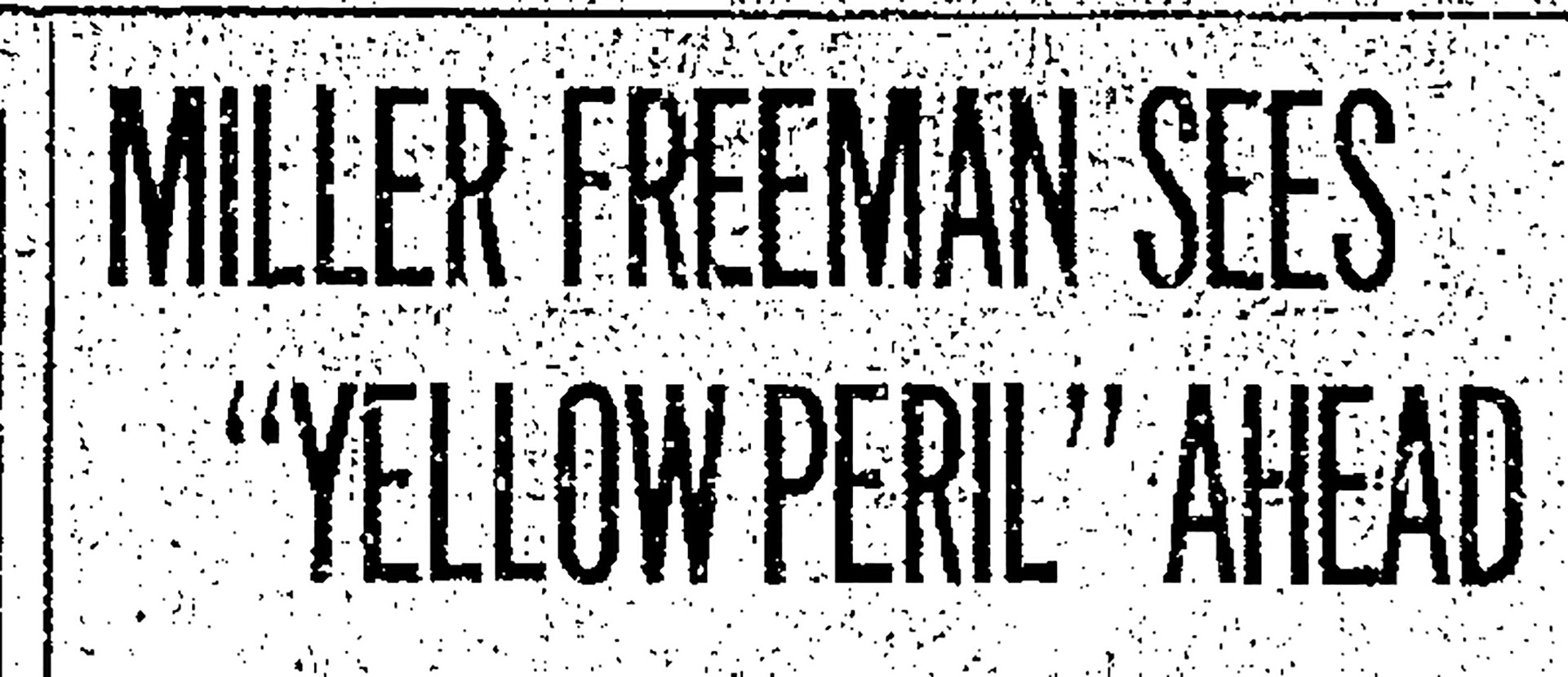

[Header image: An August 4, 1910 headline from the Seattle Times. See the full article here.]