October 28, 2020

Guest post by Miya Sommers

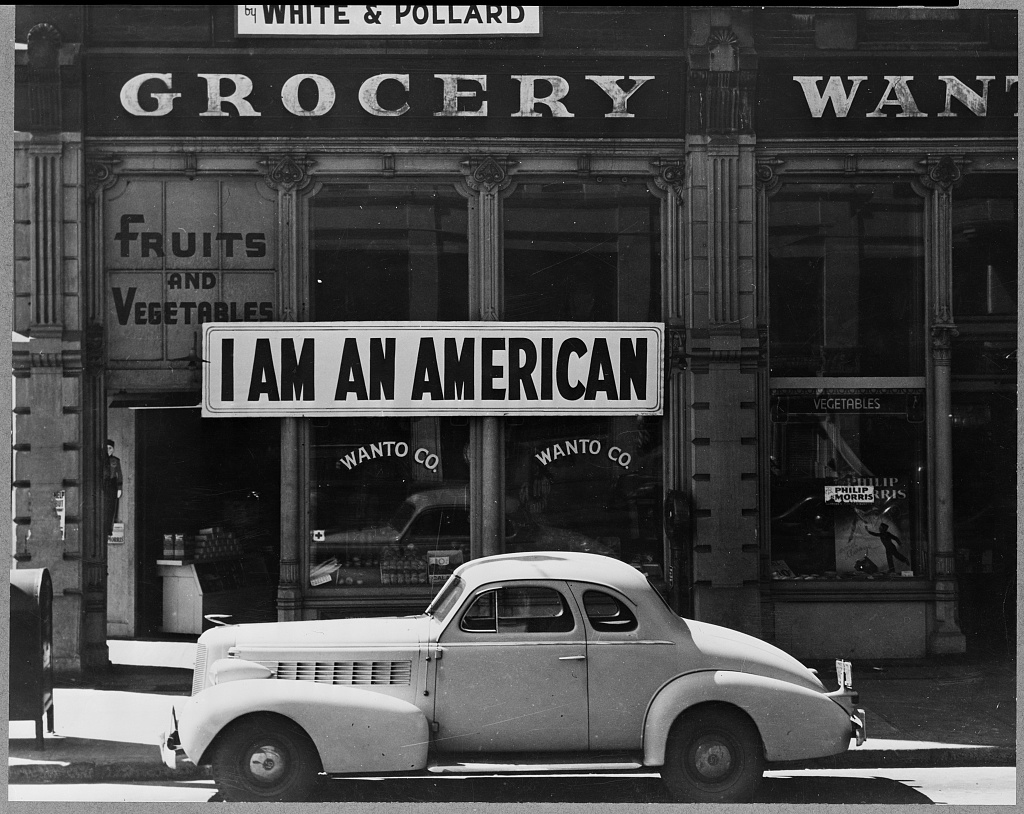

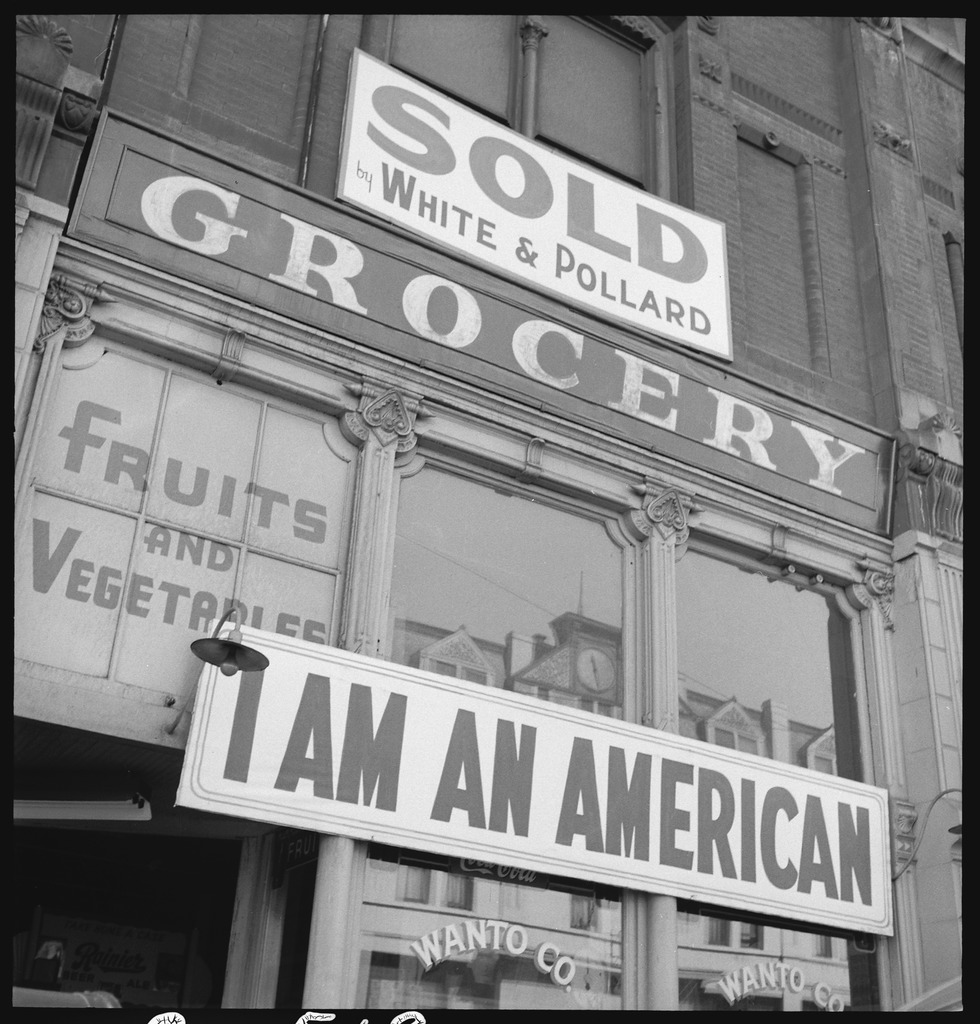

On December 8, 1941, the day after Pearl Harbor, Tatsuro Matsuda commissioned and installed the famous “I AM AN AMERICAN” sign on his family business in Oakland, California. But despite these attempts to reinforce their “Americanness,” the Matsudas were forced to close Wanto Co. just a few months later, when they were incarcerated along with 120,000 other Japanese Americans following Executive Order 9066. The now iconic Dorothea Lange photograph of that sign is a painful reminder of the systemic racism Japanese Americans experienced, even as many tried so hard to prove they were “American”—so I’m baffled to see some Asian Americans “reclaiming” Matsuda’s plea for survival as a #GetOutTheVote slogan today.

It’s a Saturday, and like any self-respecting millennial, I’m on Instagram. Scrolling through my feed, I come across a series of posts by Asian Americans wearing the same black sweatshirt with the words “I AM AN AMERICAN” written across the chest. In their captions, they talk about how, as the children of Asian immigrants, it is imperative to vote given what’s at stake this election. But I’m still puzzled at how this particular slogan is supposed to celebrate or empower Asian Americans. Doesn’t verbiage like this reinforce the dangerous perpetual foreigner stereotype? Who are we trying to remind that we are American*?

One post finally explains that the sweatshirt was inspired by the Matsudas. But even then, it only mentions when the sign was installed. It completely leaves out why the Matsudas put those big bold letters across the family storefront the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

What is missing from this story is how on the night of December 7th, Issei were rounded up by the FBI. How even before that, our people were being spied on by the government and added to “a special list of those who would be the first to be placed in a concentration camp in the event of trouble.” It ignores that Issei were ineligible for citizenship, and therefore prohibited from voting, because they were not part of the “Caucasian race.” It erases the anti-Asian xenophobia that was prolific across the country, and that when the first Asian immigrants arrived in the United States, they were never seen as fully human, merely as tools of toil for colonial expansion against Indigenous peoples.

This slogan leaves out that even after incarceration, our families were expected to assimilate. As they left the camps, they were told to avoid Japanese people, language, and culture, and urged to “develop such American habits which will cause you to be accepted readily into American social groups.” For fear of further incarceration, deportation, or death, Japanese Americans needed to be hyper-American.

“I AM AN AMERICAN” is a reminder that there is and was a very specific construction of “American,” and allegiance to it does not guarantee protection. For even as the Matsudas tried to insist on their Americanness, it could not stop the incarceration orders that were born out of institutionalized racism. This continues today as we witness a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes, fueled by vitriol seeking new scapegoats as the COVID-19 pandemic continues.

“I AM AN AMERICAN” is not a slogan to reclaim. It was a plea for survival rooted in the legacies of violence enacted by the United States. It does not offer us safety no matter how hard we try to assimilate. To move forward, we must focus not on becoming more American, but on a transformation that ensures our communities are able to thrive.

This is not to say that we shouldn’t be voting. As with every election, there is a lot on the line. We are giving individuals the power to chart the course of our histories and choosing propositions that can alter the very fabric of our neighborhoods. I appreciate the sentiment in encouraging Asian Americans to be politically engaged (although there are challenges far beyond apathy that suppress Asian American voting). But to do so using a misinterpretation and sanitization of our histories will get us nowhere.

So when we cast our votes, I hope that we Asian Americans, in all of our nuances and disaggregated, diverse legacies from the ancestral homelands, vote not to ask white supremacy for permission, but with the intent to transform what being American means.

To start, participating in the electoral process also means that we must be active in our neighborhoods and communities after November 3rd. That means remembering to turn in your ballot early, but also supporting efforts to fight voter suppression. It calls on us to be engaged in community-based organizations that believe in people power. It means that we remain committed to each other, and join spaces that center the voices of the people most harmed by institutions upheld by racial capitalism. Transformation demands that we learn our history and refuse to be tokenized, vilified, or weaponized by the state.

We Asian Americans must resist assimilation into white supremacy and loudly dream of a world that serves us all. In the words of Yuri Kochiyama, “Tomorrow’s world is yours to build.”

—

*Noting that even the use of American requires more thoughtfulness. “American” refers to the entire region of the Americas, but we in the U.S. use it to refer to being from the United States. More food for thought here.

Miya Sommers (they/she) is a gosei community organizer who is a settler on unceded Chochenyo land. Their journey to community has been framed by the resilience of their maternal grandparents who survived the WWII incarceration and the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. In navigating the inheritance of their histories, Miya has been drawn to organizing spaces that offer visions of liberatory futures. Currently, they are working on developing those spaces in Nikkei communities as a coordinator for Nikkei Resisters and as a member of Japantown for Justice, as well as having organized the first Nikkei Decolonization Tour in May 2019. Miya also works as the Assistant Director of Asian Pacific American Student Development (APASD) at UC Berkeley and is in the middle of their first semester for the Asian American Studies Master’s program at San Francisco State University.

[Header image: Dorothea Lange’s iconic photo of the Wanto Co. storefront. Original caption: “Oakland, Calif., Mar. 1942. A large sign reading “I am an American” placed in the window of a store, at [401 – 403 Eighth] and Franklin streets, on December 8, the day after Pearl Harbor. The store was closed following orders to persons of Japanese descent to evacuate from certain West Coast areas. The owner, a University of California graduate, will be housed with hundreds of evacuees in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration of the war.” Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.]